Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form

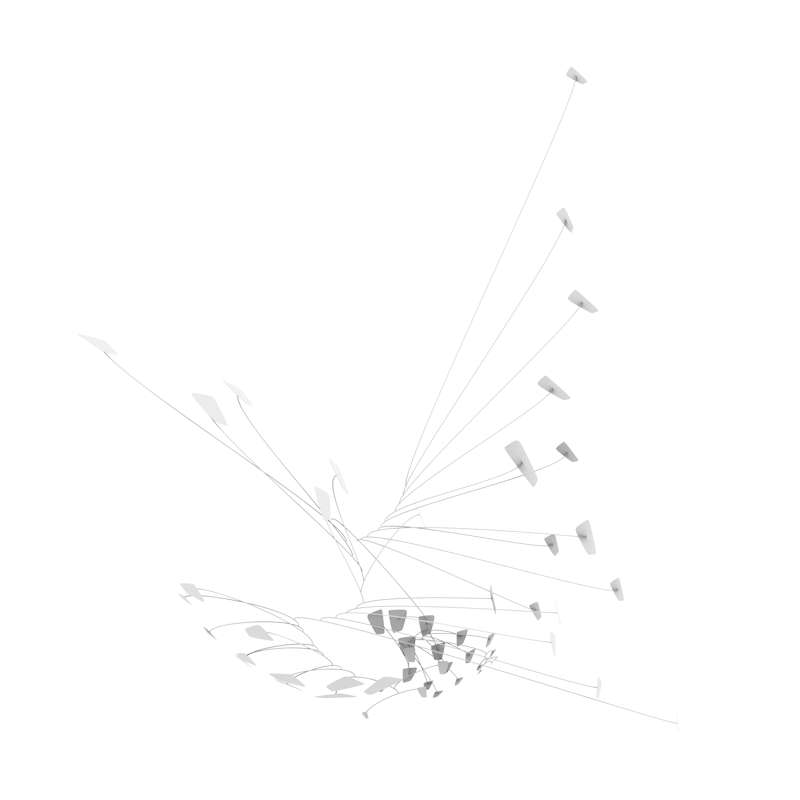

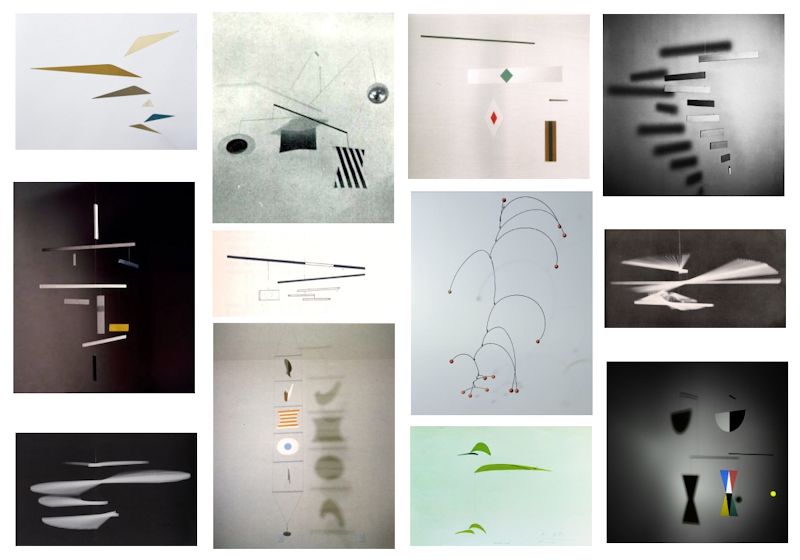

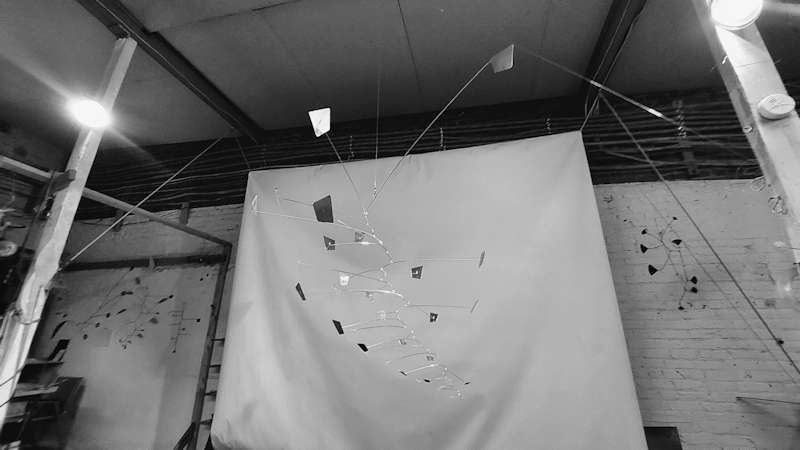

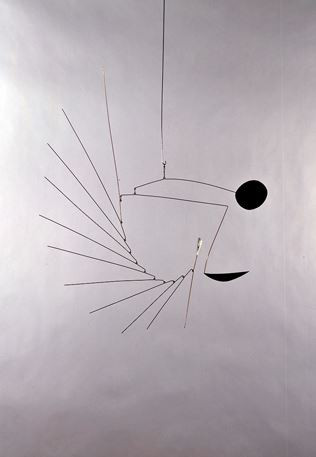

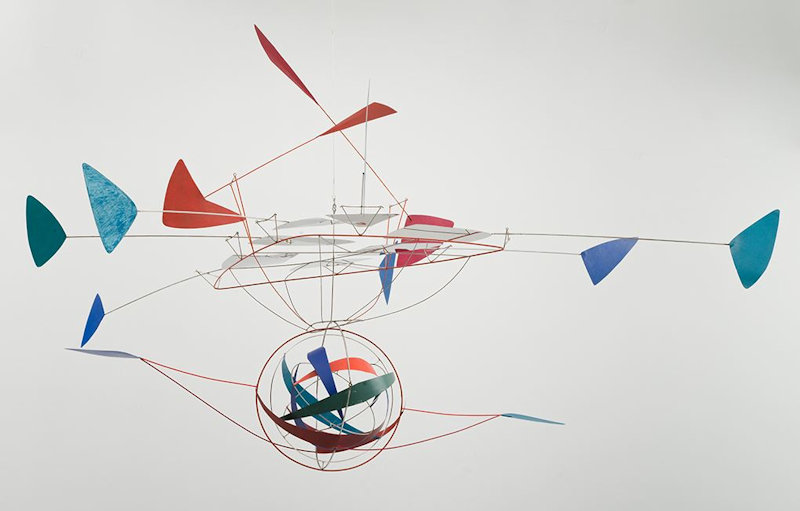

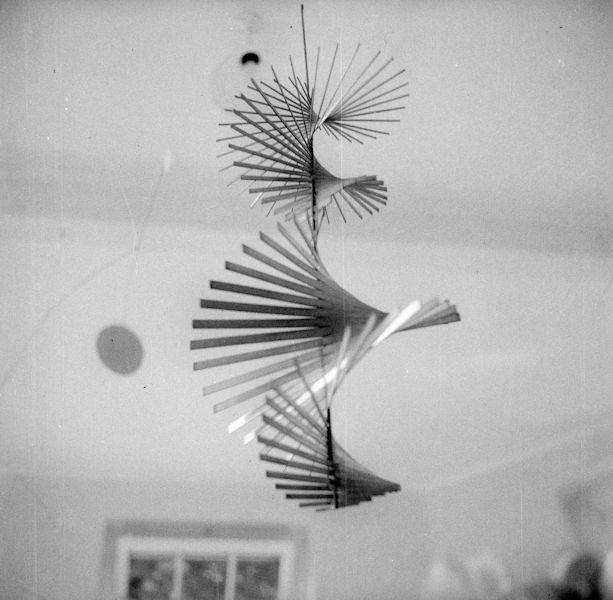

What I’m currently (2024) working on in my apparently perpetual endeavor to expand the art form of mobiles beyond the limitations of Alexander Calder‘s work: Calder described his approach to designing and making his mobiles in a conversation with Selden Rodman in 1957: “I used to begin with fairly complete drawings, but now I start by cutting out a lot of shapes. Next, I file them and smooth them off. Some I keep because they’re pleasing or dynamic. Some are bits I just happen to find. Then I arrange them, like papier collé, on a table, and “paint” them – that is, arrange them, with wires between the pieces if it’s to be a mobile, for the overall pattern.” His mobiles become three-dimensional when suspended as each part moves and rotates with the air currents. But his approach to the layout of a mobile is essentially two-dimensional, on a table. Calder’s Vertical Foliage is good example to illustrate this. However, there seems to be creative approaches to fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that Calder only very rarely ventured into (his mobile Red Cascade made in 1960 is an example). Here are some of the ideas and experiments that I’m currently working on and experimenting with, finding ways to expand his approach (and there’s also a continuation of this post Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form – Part 2):

George Rickey, while outlining the early explorations by artists into kinetic art from 1912 to 1932 in his book Constructivism – Origins and Evolution (published in 1967, and to my knowledge, the most wide-ranging and comprehensive book on the subject of Constructivism to date), remarked: “It was Calder who succeeded in securing a place for kinetic art. He started making mobiles twelve years after Gabo’s Manifesto, and his first exhibition of these was in 1932 at the Galérie Maeght in Paris. Although his mobiles have since become famous and popular and have enlarged the limits of art, his style, deriving from painterly concepts, has had little influence on the new generation, especially the more mechanically inclined. Until his stabiles of the last decade, Calder retained a two-dimensional outlook in sculpture devised as outline drawings, often witty, with ingratiating movement added. He seemed indifferent to the wide possibilities of a kinetic art. He discovered a new world but did not explore it.“

To put the idea in different words: Calder’s process began with seeing Piet Mondrian‘s paintings and feeling the impulse to make the static abstract shapes in the paintings move. He translated this idea to his mobiles quite precisely, essentially creating two-dimensional abstract paintings made of a series of flat shapes that move. Most of them only happen to become three-dimensional because these two-dimensional abstract “paintings” (essentially two-dimensional planes made of a series of flat shapes) happen to curve three-dimensionally when moved by air currents. He remained devoted to this approach with his mobiles and veered from it only very rarely, and not far when he did.

In 1962, in a review in Arts Magazine of an exhibit of Calder’s work at Tate [PDF], George Rickey wrote: “The mobile, even if flexible, is two-dimensional, like a drawing on a rubber sheet. The sinuous tracery of each set of wires profiles may sit contrapuntally against the next, but flat against flat. With the parts swinging around a vertical axis, the galaxy occupies space but does not energize it. Calder has run through the permutations of these wire profiles; yet, apart from some perfecting of wire technology, extension and refinement of his vocabulary of shapes (the Arpesque flame forms are the best), and increased size, he shows very little advance in the expressive use of movement in the thirty years since Calderberry Bush [also known as Object with Red Discs, made in 1932 and regarded as Calder’s first mobile sculpture]. It is not the first time that an artist has been confined by his own invention; it happened to Samuel F. B. Morse. The Master of the Catenaries has become the prisoner of the chain he forged.“

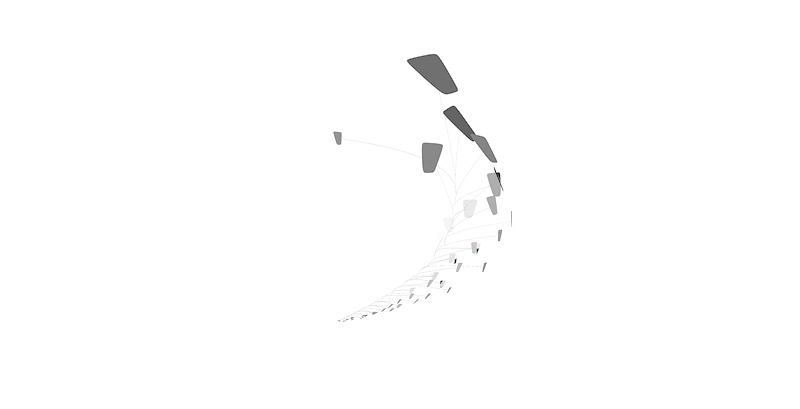

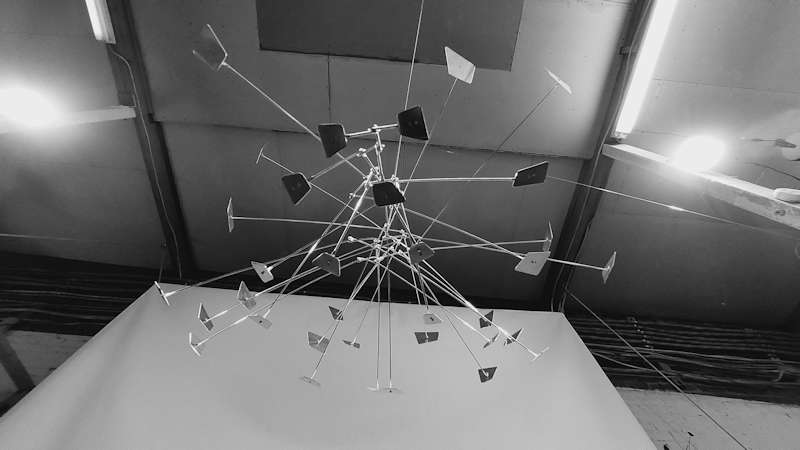

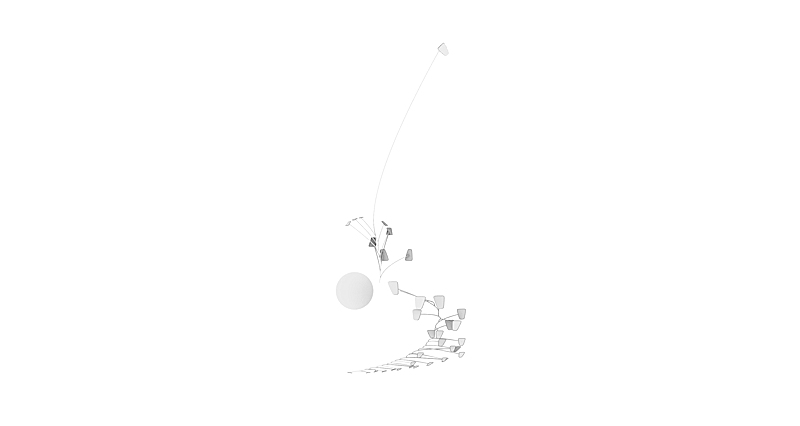

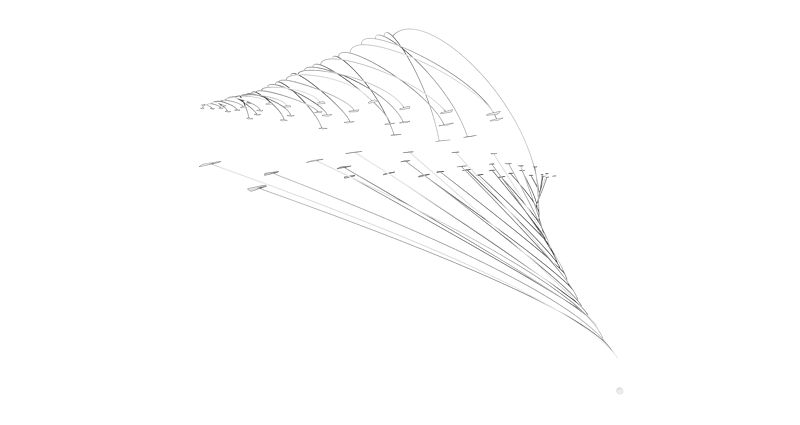

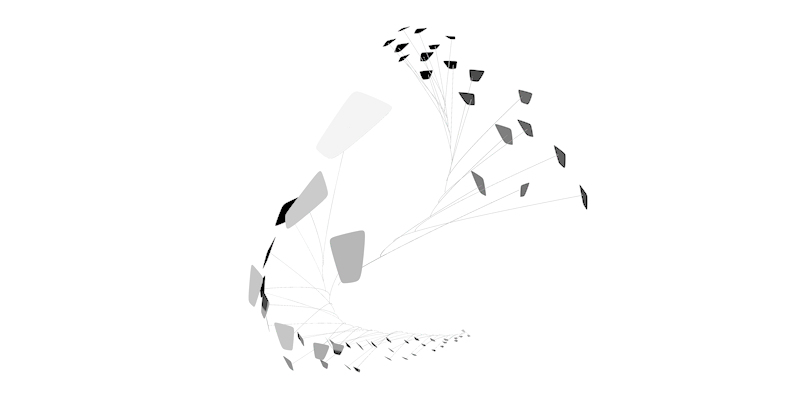

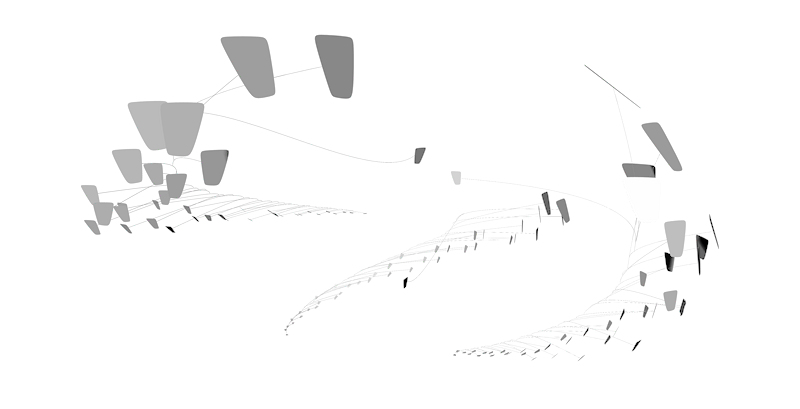

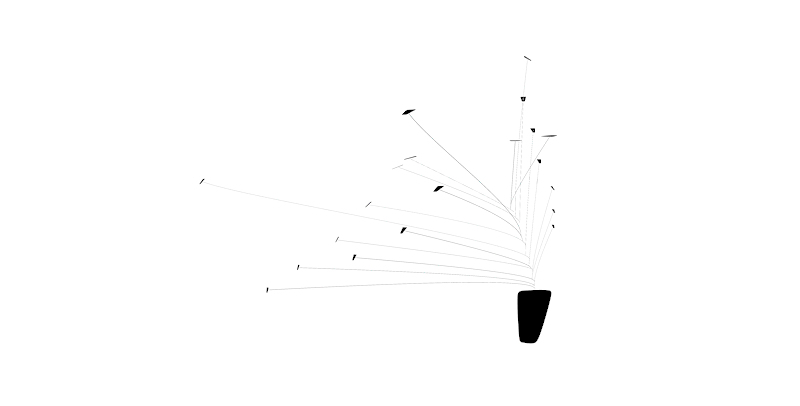

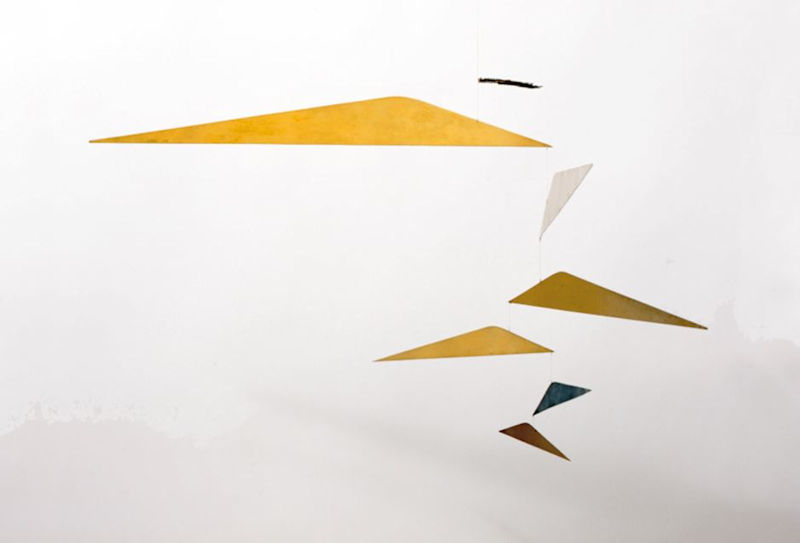

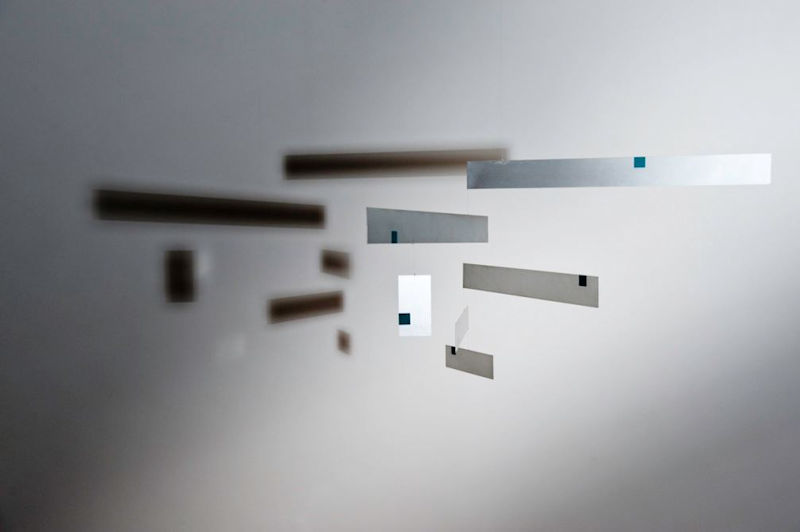

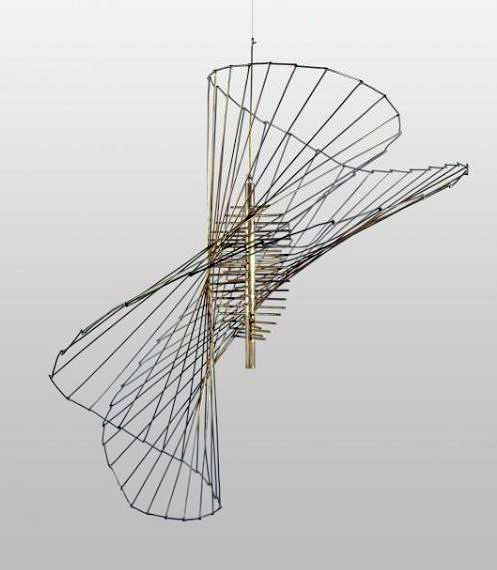

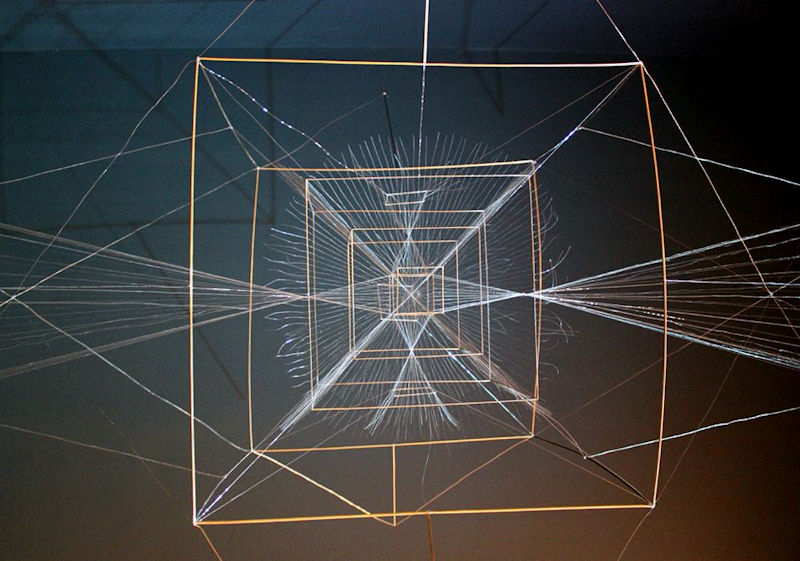

To expand Calder’s idea, one could create mobiles with the same balance structure as Calder’s mobiles (based on the whippletree mechanism), and create moving abstract “paintings” that are truly three-dimensional, not just two-dimensional planes made of a series of flat shapes that curve with the air currents.

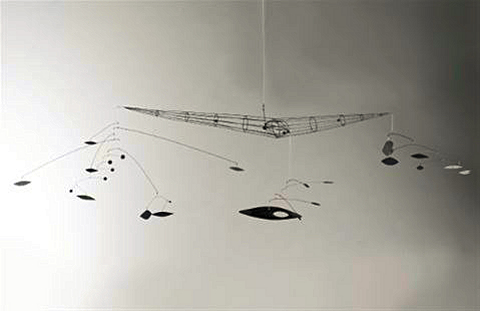

In his later years, Calder designed and made some of his mobiles consisting of two (or more) horizontal and vertical planes, each one being essentially arranged in two dimensions. His hanging mobile titled Lone Red Among Blacks (1961) is a good example to illustrate this. Here again, the three-dimensionality was a result of combining two or more “flat” two-dimensional arrangements, not of a fully three-dimensional arrangement.

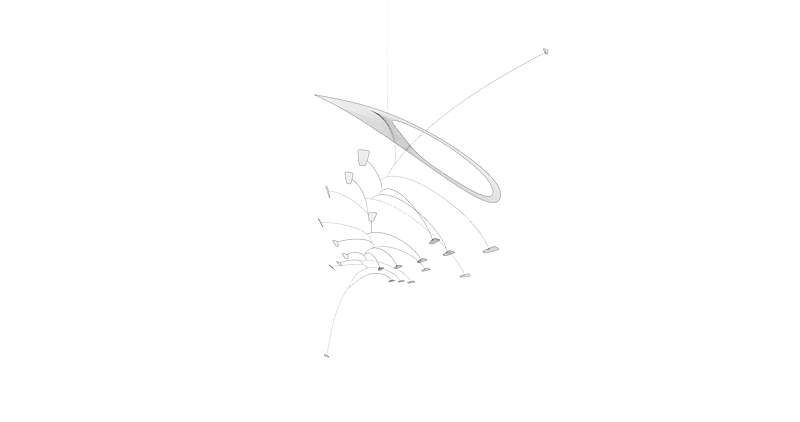

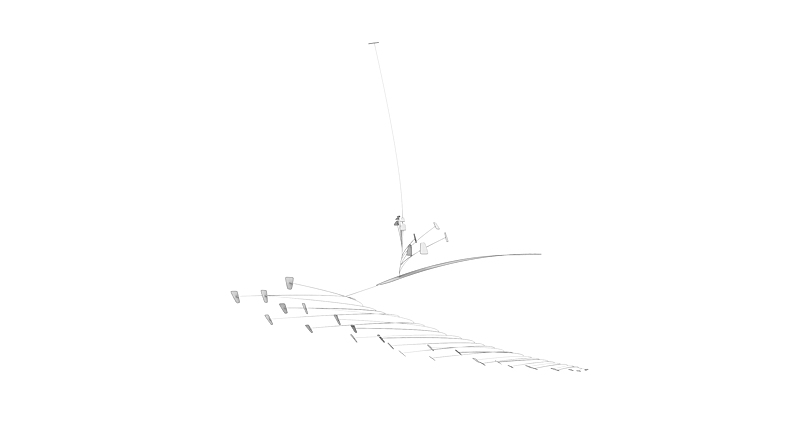

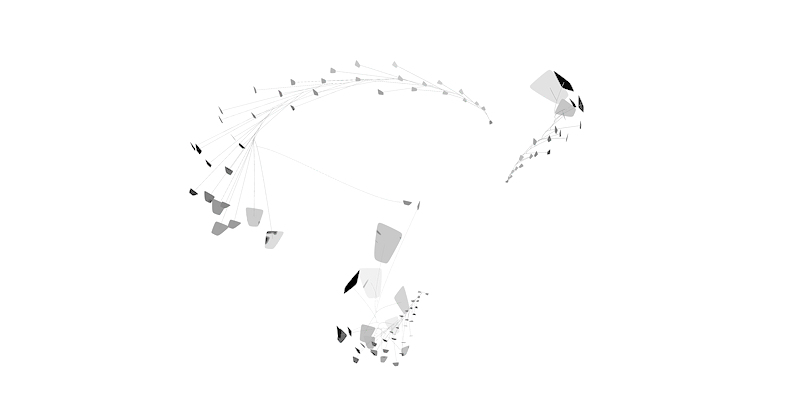

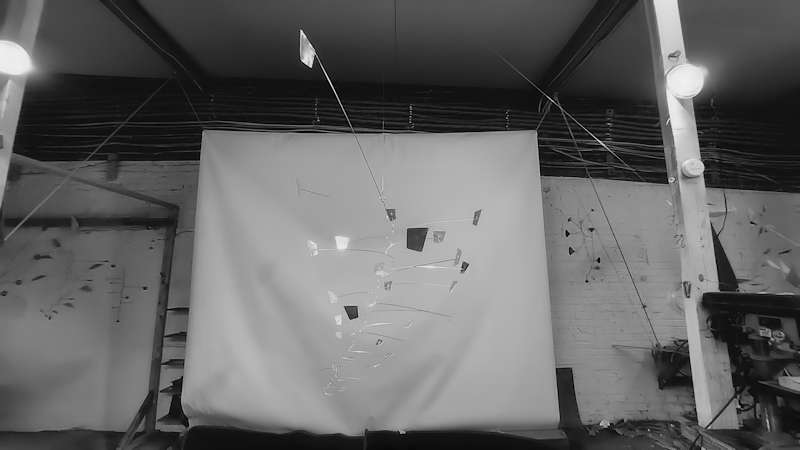

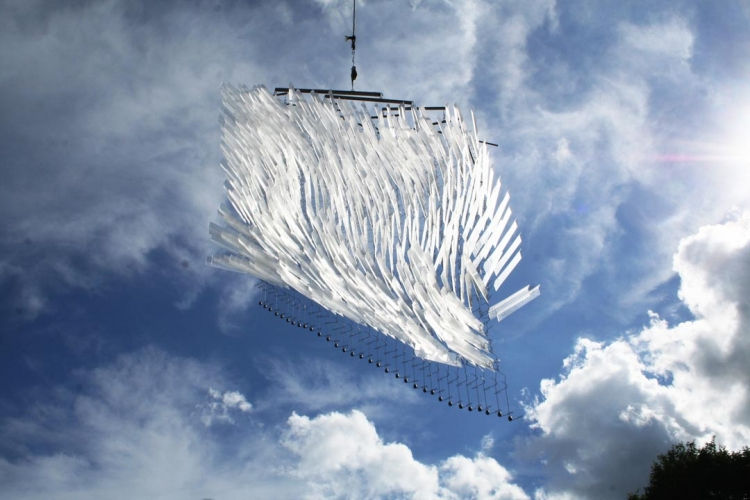

These mobiles shown here are still designed with the interconnected balance structure where the balance of each part depends on the other parts, as in a Calder mobile. And same as in Calder’s mobiles, it’s essentially an upside down whippletree mechanism, which probably dates back to between 190 to 209 AD, and has been used to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon:

Man Ray was the first artist (to my knowledge) to utilize this balance structure in a suspended sculpture with his piece titled Obstruction in 1920 (if you’d like to read more about the history of mobiles, please see my page Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles Part 1).

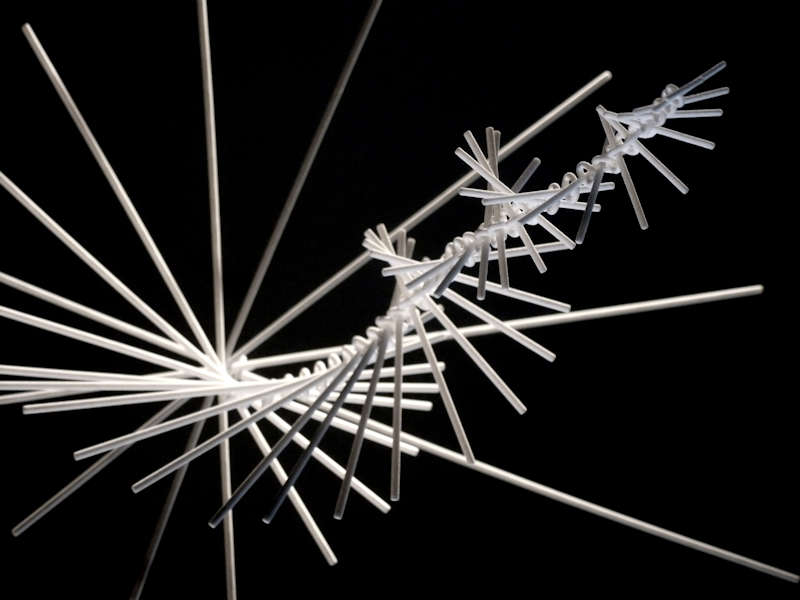

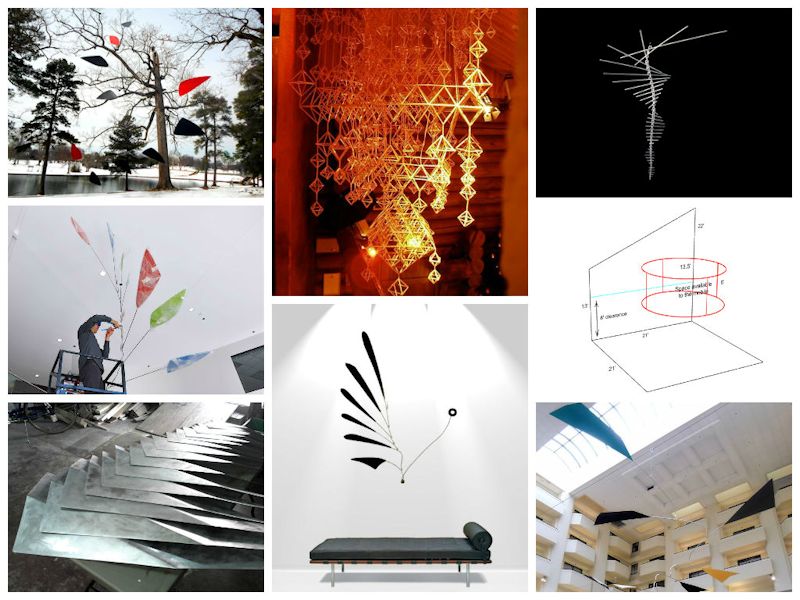

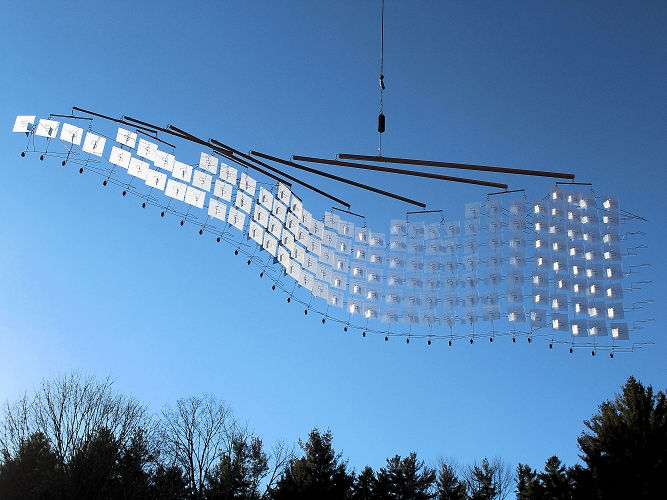

Almost all artists who have made mobiles since Calder have adapted his two-dimensional approach. Few have worked to move beyond and explore the possibilities of fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that utilize the interconnected balance structure that distinguishes them from simply suspended sculptures (please see my page Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles – Part 2 for some examples). George Rickey recognized the limitations of Calder’s two-dimensional approach to mobiles and expanded the art form, although many of his pieces don’t utilize an interconnected balance structure throughout. After around 1950, he often also opted for standing sculptures instead of suspended ones. Lynn Chadwick, Tim Prentice, Jerome Kirk, Derick Pobell, Laurent Martin “Lo”, Philippe Jestin and Jade Oakley have found ways to some extend to free the art form of mobiles from Calder’s two-dimensional approach. Tim Prentice expressed the challenge in a conversation with Nicholas Fox Weber (published by Maxwell Davidson Gallery in 2000): “Calder was credited with inventing sculpture with moving parts, so for me Rickey was incredibly important because he demonstrated that this concept wasn’t any one man’s property. I can do it to a limited degree. I can draw a line and have it curve, undulate, curl, turn, twist – in that sense, the line is changing – and I can do it with planes. The next challenge would be to do it with volume.” Volume as in three-dimensional planes instead of two-dimensional planes? Or no planes at all?

On the topic of Calder and Rickey, Tim Prentice wrote in his book Drawing on the Air – The Kinetic Sculptures of Tim Prentice: “If you compare the two, Calder was a great storyteller [and an entertainer] and not a theorist. When anyone asked him tough questions about his work, he hid behind his humor. For example, when asked how he knew a piece was finished, he famously answered, “When it’s dinner time.” He operated entirely on intuition. By contrast, Rickey was an intellectual and teacher. He was far more strict in his use of Constructivist principles. He analytically isolated movement in the way Josef Albers isolated color. [Rickey] and Calder represent the two contrasting sides of the brain.” Tim Prentice’s work greatly expands the art form of mobiles. He seems to build on Rickey’s approach more than on Calder’s. As he himself has explained: “As I concentrated on reducing weight and friction, the decisions came to be based more on engineering and less on aesthetics” and “we make the machine and keep our artistic instincts out of it and the air comes along and does the art.” Can the contrasting approaches be combined in new ways?

Building on Calder’s hanging mobile 13 Spines (1940):

Photos reverse the idea of turning an abstract painting or drawing into a three-dimensional moving sculpture. They turn it back into a flat immobile image made of abstract shapes. Two-dimensional layouts in mobiles, like many of Calder’s mobiles and the more conventional mobile sculptures I made some years ago, are easier to capture and comprehend in photos. While video can provide a solution to this, most people discover new art in the form of photos nowadays, especially now in the digital age. You can make an amazing three-dimensional sculpture, but if the sculpture doesn’t allow you to represent its idea comprehensively in images and photos, then you’re limiting the reach of the idea greatly. As Sarah Sze put it in an interview with Melissa Chiu: “In many ways, great artworks are known primarily through photos – so arguably the photos are as important as the artworks themselves.”

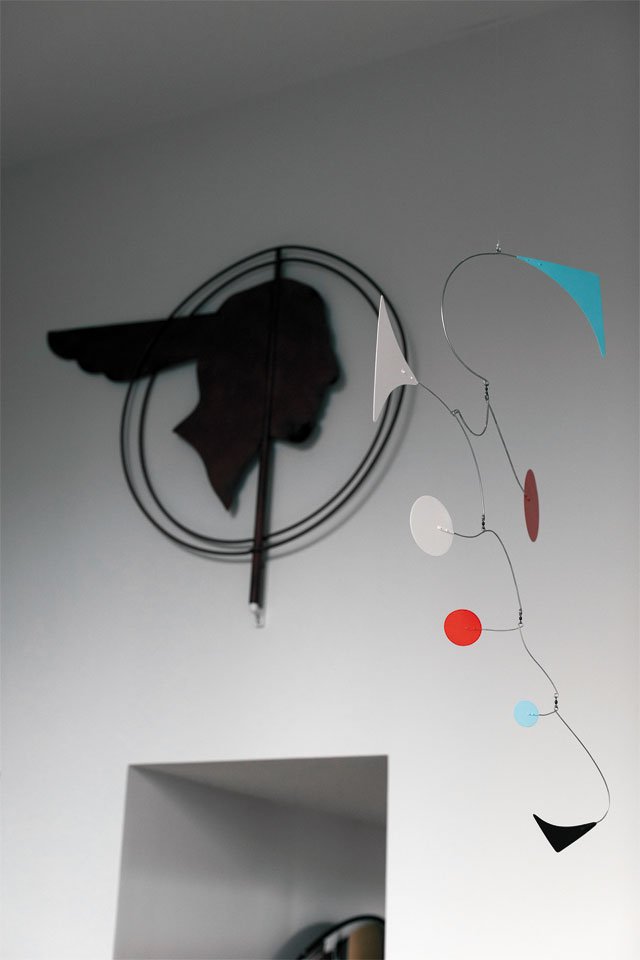

An approach that seems architectural to me:

“Paintings are but research and experiment. I never do a painting as a work of art. All of them are researches.” – Pablo Picasso, in an interview with Alexander Liberman for Vogue in 1956.

Or as architect Santiago Calatrava has pointed out: the surrealist André Breton said, “Everyone knows what a head looks like”, to which Alberto Giacometti retorted: “Not me.”

See the continuation of this post Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form – Part 2 with additional new mobile sculptures that I’m working on based on this approach.

As with anything on my website, if you have any suggestions, anything that should be added, corrected, or have any questions or comments, please let me know.

– See more of my mobiles –

Marco Mahler gives new life to the kinetic art form Calder made famous – RHome Magazine

New Article in R•Home:

Marco Mahler gives new life to the kinetic art form Calder made famous

It talks about how I got inspired by Alexander Calder’s mobiles at the National Gallery of Art’s Tower 2 in Washington, D.C. to make my first mobiles, then made small mobiles and kinetic sculptures that I sold on online, got commissioned for a series of mobiles for a New York Fashion Week, winning third prize in the 2015 International Kinetic Art Organization competition, a custom mobile for Robert A. M. Stern, New York architect and dean of architecture at Yale, collaborated with mathematician Henry Segerman to create 3D printed mobiles, a custom designed mobile sculpture that I made for the 2019 movie The Upside starring Bryan Cranston and Nicole Kidman, and some of my new ideas for suspended kinetic sculptures for future projects.

Mobiles shown in the article are Mobile 92 and one of my original contemporary mobile sculptures. Some of the 3d printed mobiles and a shape for a large custom mobile are visible in the background, as well as some of my other contemporary mobiles.

Thanks to Elizabeth Cogar and R•Home managing editor Susan Morgan!

Incidentally, a mobile that I custom-made for architect and former Dean of the Yale School of Architecture Robert A.M. Stern for his room at The Kips Bay Designer Show House is featured in the following issue of R•Home Magazine in the feature article about interior designer Doug Stiles and his condo in Richmond’s Bellevue Square where the mobile is currently suspended:

Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles (Part 2)

As a professional mobile sculptor, I continuously study other artists’ work who have also explored the art form of mobiles. On this page I’m summarizing some of the research I have done for myself. Also, this is a continuation to my previous post Mobiles before Calder – A History of Mobiles (Part 1), in which I wrote about mobiles (or mobile-like sculptures) throughout history up until the early 1930s, when Alexander Calder started to make them. This second part focuses on sculptors who have expanded the art form of mobiles from the 1930s on to present day.

Probably anyone who is familiar with mobiles as an art form knows of Calder’s work. After all, he is widely regarded as the originator of the genre, which he continues to dominate even to present-day. “Calder is a school of one”, the Daily News announced in 1972. Art critic and Los Angeles Times contributor David Pagel referred to mobiles in a Los Angeles Times article in 2012 as “a genre of sculpture [Calder] may not have invented but owns so completely that it’s almost impossible for another artist to make a mobile and not be compared, unfavorably, to Calder.” As someone who makes mobiles professionally, I believe that there are vast uncharted territories in the art form of mobiles.

Not many sculptors have applied themselves yet to the relatively new art form of mobiles over the past 100 years. However, some mobile sculpture artists (besides Calder) have created new creative approaches and expanded the art form of mobiles since the early 1930s:

Lynn Chadwick (1914-2003)

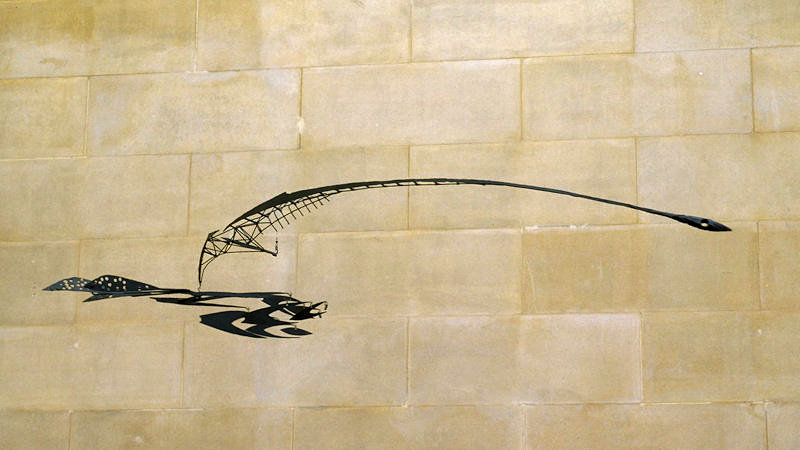

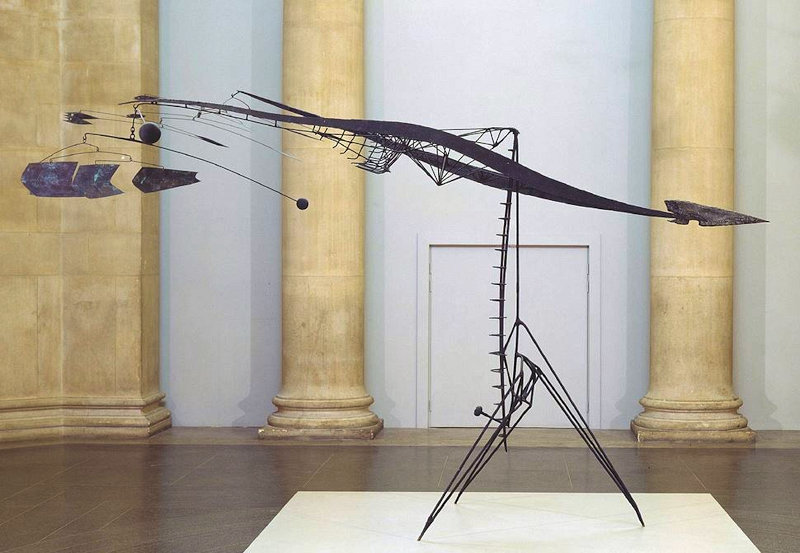

Lynn Chadwick was an English sculptor and artist. A self-trained yet extremely skilled craftsmen in metal, he is regarded as one of the major figures in the arts of the second half of the 20th century. While working with architect Rodney Thomas, he made at least sixty mobiles between 1947 and 1952, of which some were suspended and others freestanding. While Calder usually hand-cut rounded and oval painted shapes, and spaced them out in evocative patterns on simple wire frameworks, Chadwick’s geometric, interlocking shapes appeared to be cut from a single sheet and, in the 1951 mobiles, anchored by an elaborate, rigid, constructed framework made of wire, balsa wood, copper and brass. Very few of these mobiles survive. Interestingly, Chadwick always insisted that he had no knowledge of the mobiles that Calder made for 20 years previous to his, but that his mobiles had evolved in his own style from his work on exhibition stands:

Later in his career, Chadwick would commented: “So I did this suspension idea, and it took a long long time till I realized that I was doing exactly the same thing as Calder, but this was just about the time when I gave it up, because I realized that Calder was, really, better at doing what he was doing, than I was at what I was doing.”

His son Daniel Chadwick makes mobiles as well.

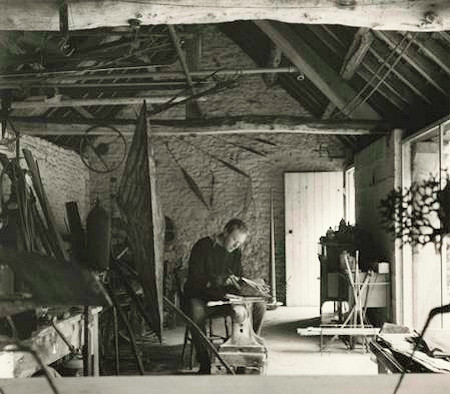

A mobile appears to be hanging on the wall in the back in Lynn Chadwick’s studio:

George Rickey (1907-2002)

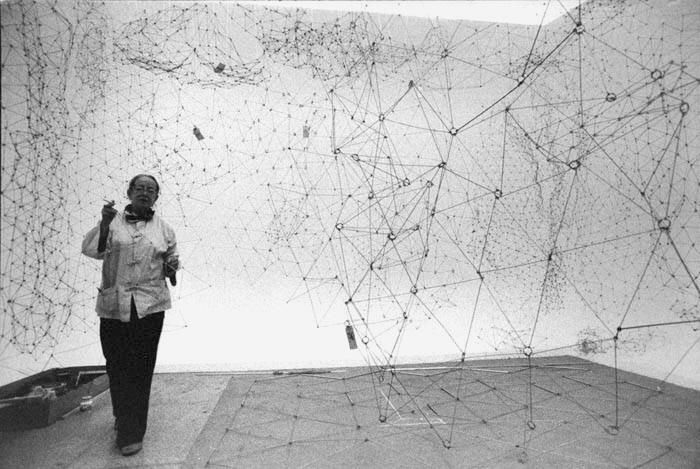

George Rickey was an American kinetic sculptor. Originally inspired by Calder’s mobiles and having served as an engineer in the Army Air Corps in World War II, he is well known for his innovative standing kinetic sculptures that respond to the slightest air currents, and whose simplicity and scale made him an important figure in contemporary art. Around 1954, he began to wonder whether Calder, brilliant and varied as his mobiles were, had said it all. “When I found he had not, I had to choose among the many doors I then found open.” Whereas in Calder’s mobiles the motion of one part is almost invariably dependent on the motion of another (usually neighboring) element, the elements in Rickey’s work are no longer hierarchical but of equal status and able to move independently and randomly in relation to each other. In George Rickey’s obituary in 2002, Ken Johnson wrote in The New York Times: “Mr. Rickey was one of two major 20th-century artists to make movement a central interest in sculpture. Alexander Calder, whose mobiles Mr. Rickey encountered in the 1930’s, was the other.” He added: “It is a curious fact of contemporary art history that Mr. Rickey left no significant artistic heirs … no sculptor has adopted his innovations with comparably persuasive ambition or elegance.” I would think Tim Prentice (see below) would strongly qualify as a significant artistic heir, as well as perhaps Susumu Shingu, and more recently Phil Price, Pedro S. de Movellán and Michael Christoph Ernst. As to Rickey and mobiles, he made them as a child already and kept returning to the art form (although after around 1950, he often opted for standing kinetic sculptures instead of suspended ones):

A standing mobile:

Tim Prentice (b. 1930)

Tim Prentice is an American architect and kinetic sculptor. Beginning in the 1970s, his work grows out of the tradition of Alexander Calder and George Rickey, both of whom he met, but it became something very original and fascinating of its own, or as he recently put it “I claimed some new territory because there was more turf to be explored”:

See a short film At Work with Tim Prentice- A studio visit with kinetic sculptor Tim Prentice.

Bruno Munari (1907-1998)

Bruno Munari was an Italian artist, designer, inventor, and author. He was interested in creating pieces of art that could interact with their environment, and made what he called “Useless Machines” (macchine inutili) of which many were essentially mobiles. Very similar to Calder’s thought process when he started to make mobiles, Munari thought that instead of painting geometric forms, why not free them from their static state and suspend them in the air:

The following suspended sculpture by Munari seems related to Ruth Asawa’s looped wire sculptures that she made only a short number of years later:

Jerome Kirk (1923-2019)

Jerome Kirk was an American sculptor. After earning a degree in mechanical engineering from MIT, he has made sculptures that measure over 45 feet in height and weigh over 6 tons, exploring a wide variety of kinetic sculptures including mobiles, both suspended and standing:

Marco Mahler (me)

I would certainly not be so arrogant to see my work as comparable to the artistic accomplishments of the other sculptors listed here, however, as opposed to just create mobiles “in the style of Calder”, expanding the art form of mobiles with new creative approaches and techniques has been the underlying motivation and passion for me in my work. I’d like to think that I’m in the process of succeeding with this, from my fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that I’m currently working on, to the deconstructivist (?) contemporary mobiles, to the fully 3d-printed mobiles that I created in a collaboration with Henry Segerman, all of which are ideas in progress that I’m working on expanding:

Philippe Hiquily (1925-2013)

Philippe Hiquily was a French sculptor and designer. After attending Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, including workshops by sculptor Jean Tinguely, he went on to make a wide variety of sculptures and furniture, including mobiles:

Additional mobile sculpture artists (besides Calder) to be added to this list who have created new creative approaches and expanded the art form of mobiles since the early 1930s would be: Laurent Martin “Lo”, Philippe Jestin, Derick Pobell, Yuko Nishikawa, Steve Haas (who combines multiple levers within one object), Jade Oakley, Brad Howe and Dylan Davis and Jean Lee.

The following suspended sculptures don’t qualify as mobiles in a strict sense, because they don’t utilize the interconnected balance structure (a whippletree mechanism as in a Calder mobile) that distinguishes a mobile from simply a suspended kinetic sculpture. However, I think the sculptures by these artists are closely related to mobiles and would be important to add to this list:

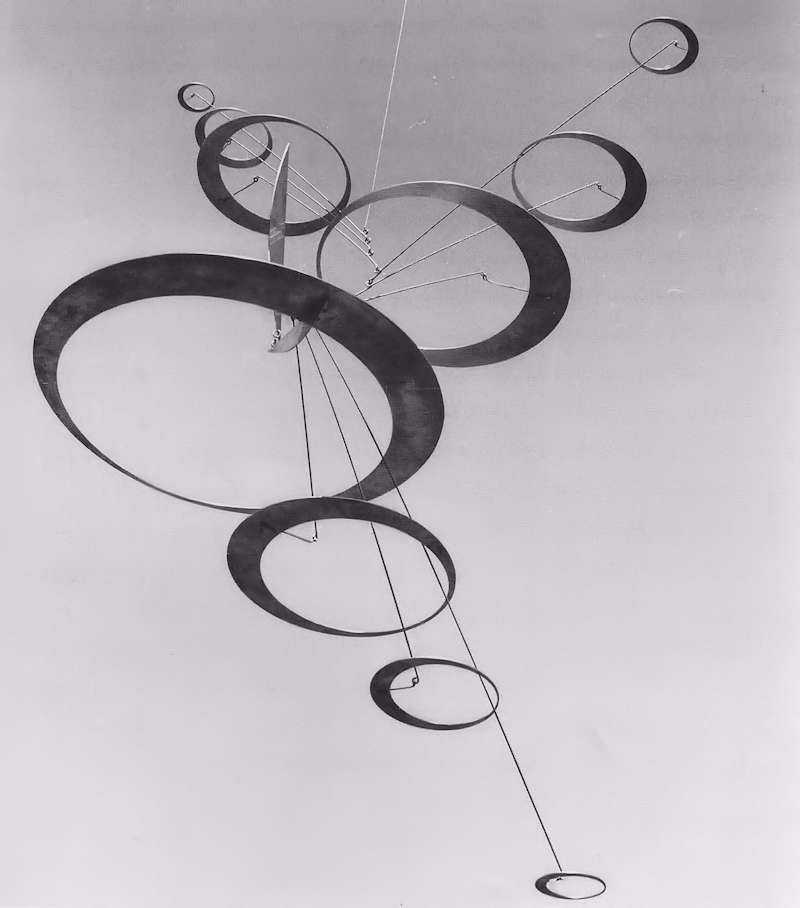

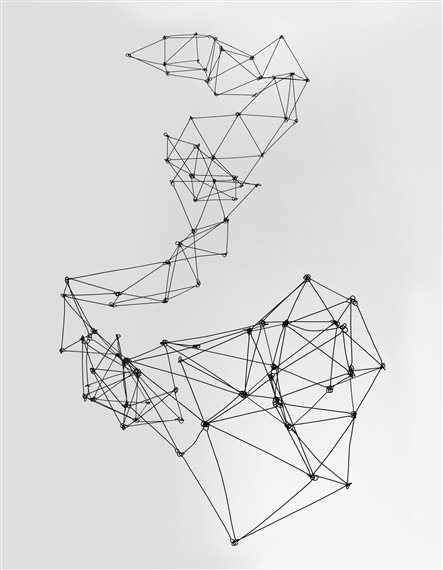

Kenneth Martin (1905-1984)

Kenneth Martin was an English painter and sculptor who (with his wife Mary Martin and Victor Pasmore) was a leading figure in the revival of Constructivism. After focusing on portraits and landscapes, his interest turned to Kasimir Malevich‘s art and geometric abstraction, which he also applied to mobiles and kinetic sculptures beginning in the early 1950s:

Among contemporary mobile artists, Miranda Watkins’ mobiles appear to be taking a similar approach as the above mobile, as well as some of the 3d printed mobiles I created in a collaboration with mathematician Henry Segerman.

Richard Lippold (1915-2002)

Richard Lippold was an American sculptor known for his geometric constructions, often relating to Cubism and Constructivism. His suspended sculptures may not qualify as mobiles, but I like them too much to not include them in this list. He spent decades stringing wires across rooms, working with architects like Walter Gropius, creating hanging sculptures that measured over 100 feet and consisted of miles of wire. The below pictured “Orpheus and Apollo”, which used to be installed at Lincoln Center, was possibly one of the largest works of public art in New York City.

In 2014, it is was dismantled for maintenance and conservation, and it will not be reinstalled at its original location. Instead, the sculpture will be suspended as the centerpiece of La Guardia Airport’s Central Hall, which is set to open in 2022.

Update – October 2023: The five-ton sculpture has been reinstalled from the ceiling of the new glass-enclosed Atrium Business and Conference Center at La Guardia (connected to Terminal B’s arrivals and departures hall) that opens next week to the public.

If you like Richard Lippold’s work, take a look at Pae White‘s work.

Gertrud Louise Goldschmidt (1912–1994), more commonly known as Gego

Gego was a modern Venezuelan artist and sculptor. I wouldn’t consider her suspended kinetic sculptures necessarily to be mobiles, at least not the ones that I’m familiar with. Yet I think the breakthroughs she contributed are, and will be, very significant to the art form:

Be sure to also take a look at the amazing work by Elias Crespin (her grandson).

Additional sculptors whose work is related to mobiles (even though their work doesn’t qualify as mobiles in a strict sense because they don’t utilize the interconnected balance structure based on the whippletree mechanism) would be: Tomás Saraceno, Elias Crespin, Reuben Heyday Margolin, Julio Le Parc, Pae White, Paul Vexler, Ralph Helmick, Hitoshi Kuriyama, Leon Jakimič (founder and owner of Lasvit), Fausto Melotti, Neil Dawson, Jean Tinguely, Antony Gormley, Matt McConnell, Jonathan and Evelyn Clowes, Mel Ristau, Ralfonso “Ralf” Gschwend, François Morellet, Jesús Rafael Soto, Ruth Asawa, Hirotoshi and Nami Sawadaand, Sarah Sze and Kendall Buster (my work space neighbor a few doors down).

Calder’s work, along with mobiles in general, has recently received renewed attention and interest, partly due to the Calder Foundation‘s excellent management of Calder’s body of work and arrangements of brilliant shows worldwide. His mobiles keep setting new records at auctions, selling in the tens of millions of dollars. In 2014, the Art Newspaper wrote about that year’s world-renowned art fair Art Basel in Miami Beach: “The number of mobiles by Calder and other artists on galleries’ stands is striking. Among the works by the hundreds of artists brought by 267 galleries from 31 countries, mobiles definitely constitute a trend.”

Aside from the art form of mobiles, Calder was also a pioneer in making wire sculptures starting in the 1920s, making portraits out of wire of public figures, entertainers, close friends and himself. He also made wire sculptures for his Cirque Calder and of animals, often sprinkled with a bit of humor. One story has it that Calder presented himself at an exhibition venue at Harvard with no work. According to Calder, the gallery director “protested that I arrived with nothing but a roll of wire on my shoulders and pliers in my pockets”. By the time the show opened a few days later, Calder had created all the works for the show on the spot, while interacting with gallery personnel, patrons, and friends. Artists such as Ruth Asawa, Kendra Haste, Sophie Ryder, Edoardo Tresoldi, Kue King and Tomohiro Inaba have expanded the art form of wire sculptures since.

I’ll be adding to this list from time to time. As a continuation, please see my page Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form.

This article was originally published on my blog here on this website in 2017. As with anything on my website, if you have any suggestions, anything that should be added, corrected, or have any questions or comments, please let me know.

Related:

Artsy article: 7 Artists Who Created Innovative Mobiles—beyond Alexander Calder

New York Times article by Nancy Hass: How Artists Are Challenging Alexander Calder’s Mobiles

New Article I Wrote Is Featured on Houzz Today: “Art in Motion: The Story behind Mobiles”

Houzz is featuring a new article I wrote today: Art in Motion: The Story Behind Mobiles. It covers topics such as what mobiles are, the history of mobiles (including Alexander Calder of course), fine art mobiles, mobiles today, and how I became a professional mobile maker.

Versions of this article also appear on my website and on Saatchi Art (via Artsy on FB and Twitter and via Saatchi Art on FB and Twitter).

– Read of my blog about mobiles –

Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles (Part 1)

As someone who makes mobiles professionally and has spent quite a lot of time studying mobiles, I get asked once in while, where did mobiles originate from? Who made the first mobile? Or, who invented mobiles? The short answer is that Alexander Calder is the originator of mobiles, which is mostly correct, but Calder wasn’t the first one nor the only one to experiment with the art form. The problem with providing a definite answer to the question of who made the first mobile starts with the definition of what a mobile is, and what is simply just a hanging kinetic sculpture made of individually suspended objects rather than being constructed with an interconnected balance structure that defines a conventional mobile. You can read my definition of what a mobile is on my main page, but there isn’t really a set of rules that one can apply to clearly tell one from the other. The first person, that I’m aware of, to clearly utilize the interconnected balance structure in a suspended sculpture wasn’t Calder. It was Man Ray with his piece titled Obstruction made of coat hangers in 1920, 10 years before Calder started to make mobiles. Man Ray also met Calder in Paris in the late 1920s, attended a performance of Cirque Calder in June 1929, shortly before Calder started to make mobiles, and made portrait photos of Calder around the same time . And there a examples of suspended sculptures before Man Ray’s piece that began to explore the idea of an interconnected balance structure. Following are the hanging kinetic sculptures that I’m aware of that were made before Calder started to make mobiles. Some of them clearly qualify as mobiles in my opinion, others are up for debate.

In chronological order:

I’ve heard of a Greek architect who built a floating statue in the 2nd century B.C. for the wife of Egyptian King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (B.C.284-246). The suspended sculpture was dependent on the overall setting of magnetic forces on the roof and the walls. I’ve been trying to find out more about this but without success.

Wind chimes have probably been around since prehistoric times. The first evidence of them, found at archeological sites in South East Asia, dates them to about 3000 B.C.. The oldest one I have been able to find an image of is from ancient Rome where people made them out of bronze. They called them Tintinnabulum and hung them outdoors so the wind would make the bells ring. They were also believed to ward off evil spirits.

Himmelis are traditional sculptures that originated in Finland, although the root of the name is Germanic. They are a decorative objects, usually made of straw, that hang from the ceiling. A Himmeli (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) is usually symmetrical and pyramid-shaped and rotates slightly with the air flow. Traditionally, they were made in the fall and were placed above the dining table until summer to ensure a good crop for the coming year. I haven’t been able to find out how far back in history the tradition goes, but they have definitely been around long before 1930 when Calder started to make mobiles.

If you’d like to make a Himmeli yourself, the Guardian has a How To Make A Himmeli Sculpture.

The Museum Van Het Nederlandse Uurwerk in Zaandam, Netherlands has a mobile dated to 1751 made of four small whale hunter boats circling a whale:

Calder was also interested in 18th century toys that demonstrate the planetary system.

From 1918 through 1921, Russian artist Aleksandr Rodchenko made some of the first suspended kinetic sculptures of the 20th-century with three series of spatial constructions, each comprised of six works. Regrettably, most of them have long been known only through photographs made at the time and through Rodchenko’s own sketches on a page of his notebook. Here is his Oval Hanging Construction No.12:

He considered them “lab work” rather than art objects and were made to demonstrate theoretical concepts.

Rodchenko’s suspended sculptures at the Second Spring Exhibition of the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) in Moscow in 1921:

The Russian sculptor Naum Gabo began to experiment with kinetic sculptures in 1917, which makes him a pioneer in the art form. He was interested in making sculptures that continually change their appearance, but are constant in what they represent (much like mobiles). The majority of his work was lost or destroyed, but here is a 1918 drawing that he titled Sketch for a Mobile Construction:

In 1915, Russian painter and architect Vladimir Tatlin made a suspended sculpture called Contre-Reliefs Liberes Dans L’espace. Constructed of mathematically interlocking planes, it apparently looked like a mobile. The details surrounding Tatlin’s life and work are relatively obscure. Here is his Letatlin (1930):

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Naum Gabo and Vladimir Tatlin (who all knew each other) were pioneers of the art movement known as Constructivism, a term that first appeared in Gabo’s Realistic Manifesto of 1920. The movement had a great effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. On the topic of Calder and Constructivism, Jed Perl notes in his biography of Calder: “Commentators who knew Calder in the 1930s, most significantly James Johnson Sweeney and Alfred Barr, argued that he owed a significant debt to the work done by the Russian avant-garde in the years before and after World War I, work often characterized by the artists and their supporters as Constructivist. Rodchenko’s hanging sculptures, Tatlin’s Monument on the Third International, and works by Gabo were mentioned. Even earlier, the German critic Adolf Behne, writing about the Neumann-Nierendorf show in 1929, had related Calder’s work to the experiment of the Russian Constructivists. But there is a problem with the genealogy of Calder’s first abstract works as it was articulated by Barr and Sweeney. As early as 1934, in a letter to the collector Albert Gallatin, Calder asserted that he had known nothing about any of these works or for that matter about Constructivism in general until Hélion told him about all of it in 1933. Surely Calder’s own testimony that pushed his friend Sweeney, in 1938, to observe that although Calder’s work was “built on a Constructivist foundation,” the artist “nevertheless had no connection with Russian Constructivism except in the fundamentals of its structure” – a statement that, to say the very least, is hard to parse. To the end of this life, Calder insisted that he had known nothing about the Constructivists in 1931. Sometime in the 1960s or 1970s, in a letter to a young art historian, Nanette Sexton (who also happened to be his grand-niece), Calder observed that “crabby guys before this have said that I must have known about the Russian Constructivists – but it’s quite untrue, i.e. I knew nothing about them till after having made some of my first mobiles.”

Now this next one is very important for the history of mobiles. It’s Man Ray‘s Obstruction that he made in 1920. It employs the whippletree mechanism as a balance structure in the same way that Calder started to use it in some of his mobiles a decade later. The whippletree mechanism probably dates back to between 190 to 209 AD, and has been used to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon:

Man Ray’s Obstruction is the first of this type of hanging kinetic sculpture that I’m aware of that makes use of this mechanism. Even with it’s rudimentary coat hanger design, it can definitely be classified as a mobile:

And just because it’s so important to the evolution of mobiles, here’s another photo of it (63 wooden hangers, recreated in 1961):

As mentioned above, Man Ray met Calder in Paris in the late 1920s, attended a performance of Cirque Calder in June 1929, shortly before Calder started to make mobiles, and took portrait photos of Calder around the same time. Here are Man Ray’s instructions on how to assemble his mobile:

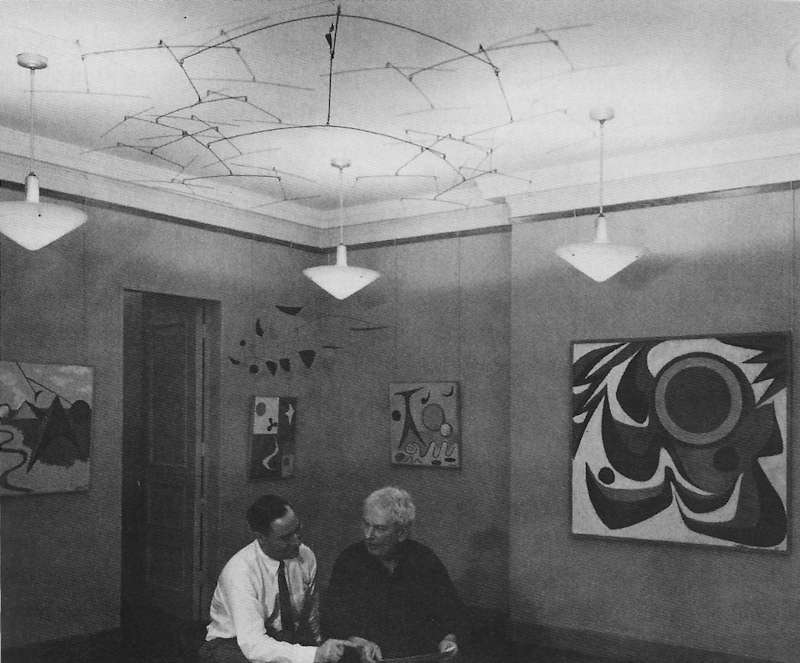

Here’s Calder (with Klaus Perls) at Calder’s 1956 exhibit at Perls Galleries with his mobile Untitled (Mobile with N Degrees of Freedom) that he made in 1946 suspended from the ceiling, which is essentially the same sculpture as Man Ray’s Obstruction (1920), just made with wire instead of coat hangers:

Many years later in 1974, Calder also created a tribute to Man Ray for a suite of prints, Hommage à Man Ray. As noted by the National Portrait Gallery: “With its odd assortment of images, this tribute to the eighty-four-year-old Man Ray reads like a private joke between two friends. Calder fondly recalled his early days in Paris when he hung out with “quite a gang,” which included Man Ray and Kiki, the “Queen of Montparnasse.”

Man Ray also experimented with hanging abstract pieces of sheet metal, here with his Lampshade in 1920:

Bruno Munari, one of the first kinetic sculptors, started to follow the Futurist movement in 1927. He made what he called “Useless Machines” (macchine inutili) and was interested in creating pieces of art that could interact with their environment (much like mobiles).

Bruno Munari’s Macchina Aer0ea (aerial machine), 1930:

Bruno Munari continued to make very beautiful and original mobiles throughout the 1930s and 1940s (same time frame as Calder was exploring the art form):

Bruno Munari once said (from the book Bruno Munari: Air Made Visible): “What difference was there between my useless machines and Calder’s mobiles? I think I should clear up this matter: apart from the fact that the material construction was different, the means of constructing the objects was also different. The only thing they have in common is that they are suspended objects that move. But there are many suspended objects and there always have been, apart from the fact that even my friend Calder had a precursor in Man Ray, who in 1920 constructed an object on the same principle.”

See more of Bruno Munari’s work if you’re interested, it’s quite amazing.

Paul Klee was reported by Lyonel Feininger to have had little mobiles in his Bauhaus (1919 to 1933) studio in Dessau, however, I’m unable to find any additional information nor images of them.

According to the Museum of Modern Art, one of Alberto Giacometti‘s achievements was to enlarge the mobile concept decisively, so that formal innovation could be reconciled with the Surrealist interest in subconscious associations. Here is his kinetic sculpture, Suspended Ball, 1930:

And now here comes Alexander Calder in 1931 experimenting with abstract motorized constructions like Mobile (Motorized Mobile):

Calder visited the painter Piet Mondrian in October 1930 and later said: “When I looked at his paintings, I felt the urge to make living paintings, shapes in motion.” Influenced by the abstract work of Mondrian, Joan Miró and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, he’s approaching the idea of kinetic sculptures like an alchemist with pieces like Object with Red Discs (also known as Calderberry Bush even though Calder claimed he never assigned that title to it), made in 1932 and regarded as his first standing mobile:

And considered by some to be his first hanging mobile (and also one of his rarer sound / “noise” mobiles), Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/33):

And in 1933, Cône d’ébène, one of his first hanging mobiles where all the elements are suspended:

Calder made a simple yet very important advance in how the balance structure is applied to a hanging kinetic sculpture. He went from the straightforward whippletree structure, like the one in Man Ray’s Obstruction mobile that we looked at above, to this (Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1932):

Instead of attaching lower elements to both ends of the wires, he replaces one on each arm with an abstract shape. It’s a new way to apply the whippletree structure to a hanging kinetic sculpture, which allowed him to turn the whole idea into a new art form, a complete new magical universe with mobiles like Vertical Foliage (1941):

The term “mobile”, a French pun meaning both “mobile” and “motive”, was coined by the master inventor of Dada, Marcel Duchamp, while visiting Calder’s studio in 1931, although he apparently already used the term in 1913 for his readymade Bicycle Wheel, which some consider to be the first kinetic sculpture.

George Rickey wrote in his review of Calder’s retrospective at London’s Tate Gallery titled Calder in London in 1962: “Calder’s fame and place in history have been secure for a long time. Outside his country, he is the most famous American artist … In Holland any moving sculpture is called “a Calder.” … Though he did not invent moving sculpture, he demonstrated to critics, historians, collectors, the man in the street, and to other artists, that it was inevitable. One need not dwell on the endless imitations and perversions of his inventions and of his style. He has delighted the world. But with what? What is he? Is he good? Is he, though a success as a popular entertainer, a superficial artist? Is he the lucky (or unlucky) stumbler on the right thing (getting sculpture into the air) at the right time, who has been trapped by his luck, or is he one of the great innovators of the epoch? Is he possibly a frustrated painter, able, through a mechanical device, to make a reasonable facsimile of sculpture? Why does a lot of Calder seem less impressive than a single piece? Is there a Calder myth?”

If you know about any other early mobiles, standing or hanging, or suspended kinetic sculptures that were made before the early 1930s, please let me know, I’d love to hear from you.

This article was originally published on my blog here on this website in 2014. Modified versions of this article also appear on Houzz, Saatchi Art (via Artsy on FB and Twitter and via Saatchi Art on FB and Twitter), Widewalls and WIRED.

Forbes article linking to this article: Seattle Art Museum Becomes the Alexander Calder Destination with Shirley Family Collection

Next: Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles (Part 2) – a list of sculptors and specifically mobile artists (besides Calder) who have made important contributions to the art form since the early 1930s.

Artsy article: 7 Artists Who Created Innovative Mobiles—beyond Alexander Calder

Related article on My Modern Met: Art History: The Evolution of Hypnotic Kinetic Sculptures

New York Times article by Nancy Hass: How Artists Are Challenging Alexander Calder’s Mobiles

– See some of my mobiles or read more of my blog about mobiles –