Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form

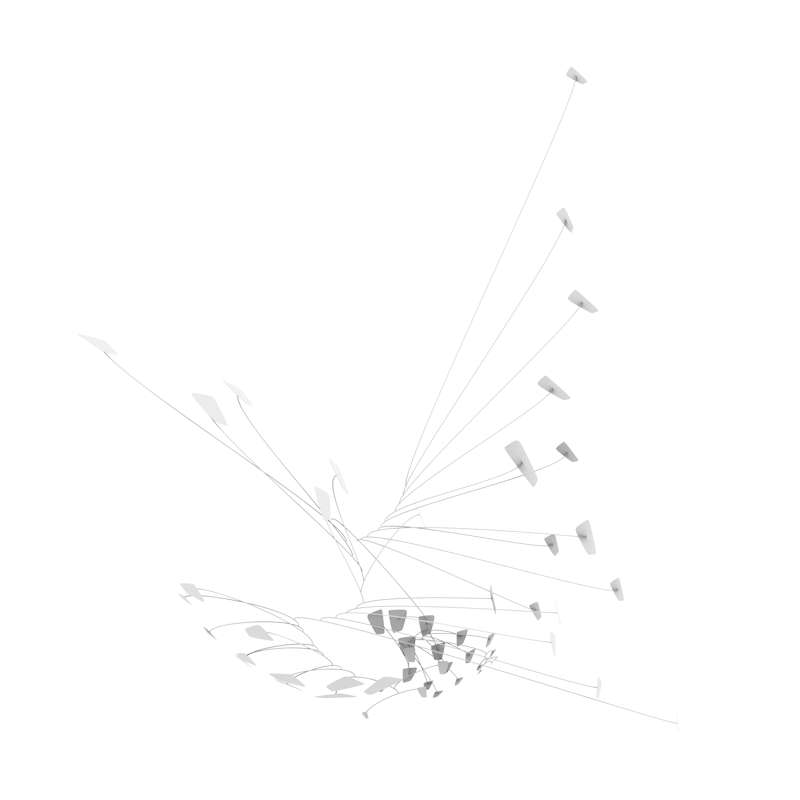

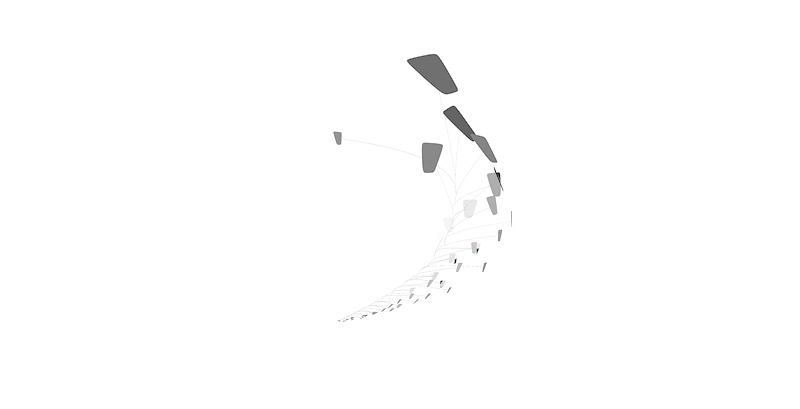

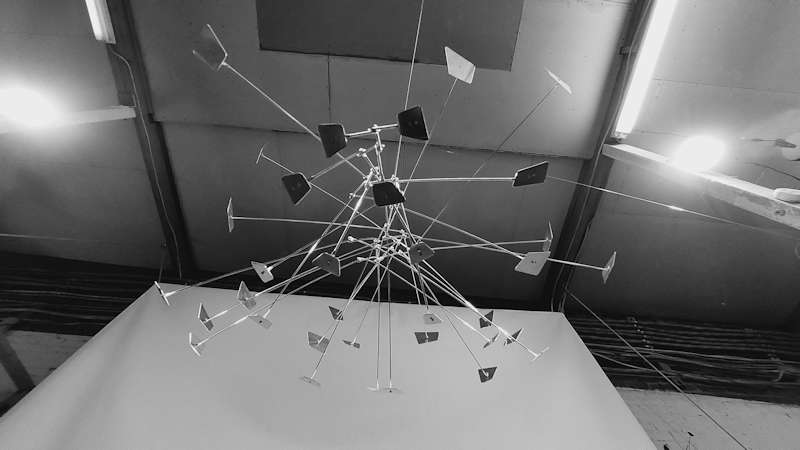

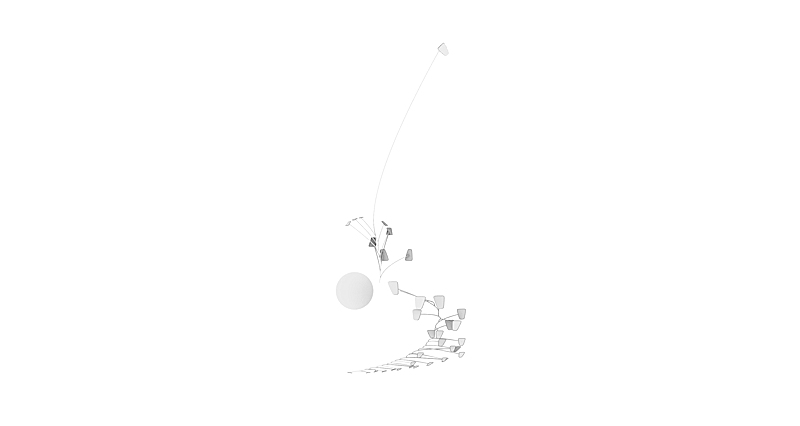

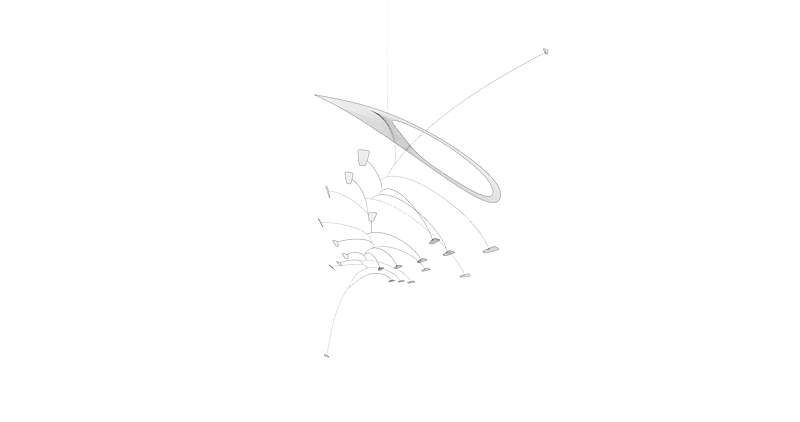

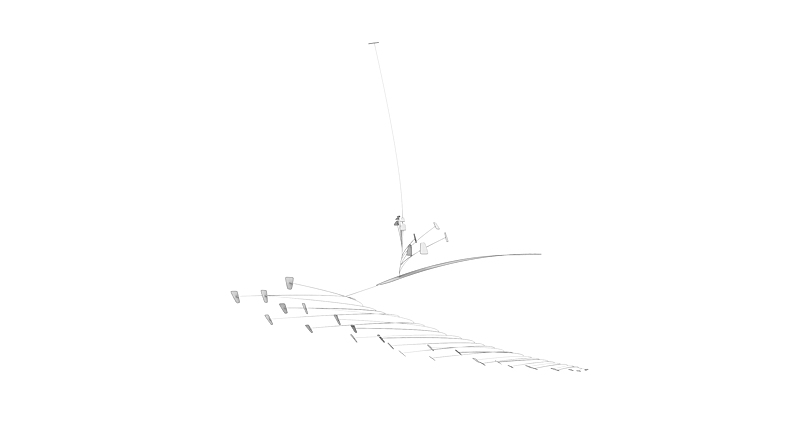

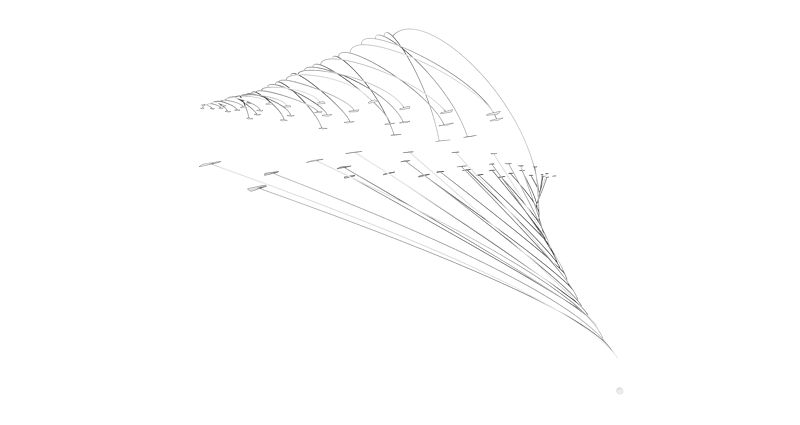

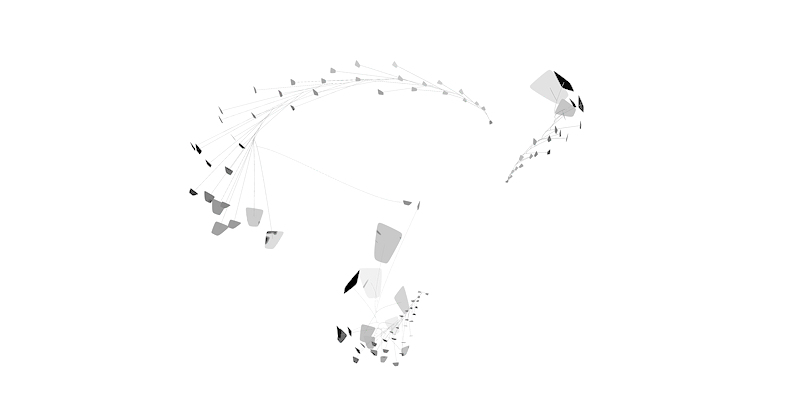

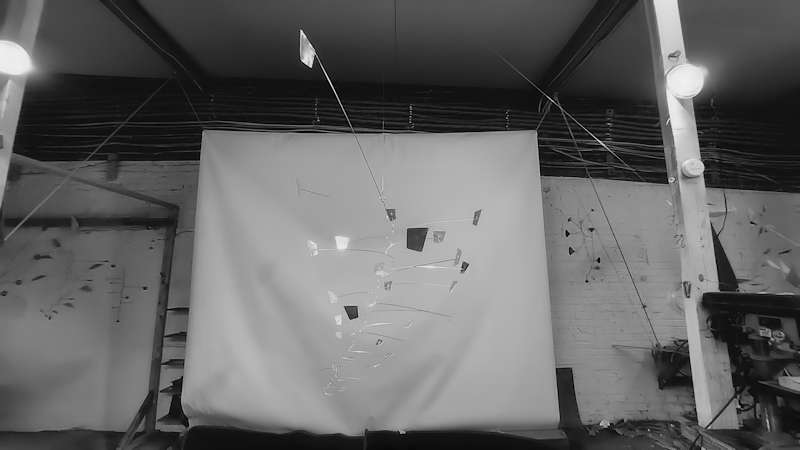

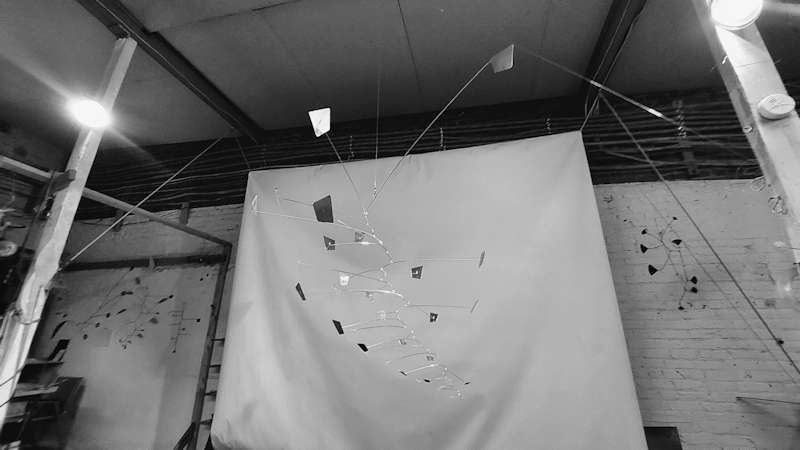

What I’m currently (2024) working on in my apparently perpetual endeavor to expand the art form of mobiles beyond the limitations of Alexander Calder‘s work: Calder described his approach to designing and making his mobiles in a conversation with Selden Rodman in 1957: “I used to begin with fairly complete drawings, but now I start by cutting out a lot of shapes. Next, I file them and smooth them off. Some I keep because they’re pleasing or dynamic. Some are bits I just happen to find. Then I arrange them, like papier collé, on a table, and “paint” them – that is, arrange them, with wires between the pieces if it’s to be a mobile, for the overall pattern.” His mobiles become three-dimensional when suspended as each part moves and rotates with the air currents. But his approach to the layout of a mobile is essentially two-dimensional, on a table. Calder’s Vertical Foliage is good example to illustrate this. However, there seems to be creative approaches to fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that Calder only very rarely ventured into (his mobile Red Cascade made in 1960 is an example). Here are some of the ideas and experiments that I’m currently working on and experimenting with, finding ways to expand his approach (and there’s also a continuation of this post Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form – Part 2):

George Rickey, while outlining the early explorations by artists into kinetic art from 1912 to 1932 in his book Constructivism – Origins and Evolution (published in 1967, and to my knowledge, the most wide-ranging and comprehensive book on the subject of Constructivism to date), remarked: “It was Calder who succeeded in securing a place for kinetic art. He started making mobiles twelve years after Gabo’s Manifesto, and his first exhibition of these was in 1932 at the Galérie Maeght in Paris. Although his mobiles have since become famous and popular and have enlarged the limits of art, his style, deriving from painterly concepts, has had little influence on the new generation, especially the more mechanically inclined. Until his stabiles of the last decade, Calder retained a two-dimensional outlook in sculpture devised as outline drawings, often witty, with ingratiating movement added. He seemed indifferent to the wide possibilities of a kinetic art. He discovered a new world but did not explore it.“

To put the idea in different words: Calder’s process began with seeing Piet Mondrian‘s paintings and feeling the impulse to make the static abstract shapes in the paintings move. He translated this idea to his mobiles quite precisely, essentially creating two-dimensional abstract paintings made of a series of flat shapes that move. Most of them only happen to become three-dimensional because these two-dimensional abstract “paintings” (essentially two-dimensional planes made of a series of flat shapes) happen to curve three-dimensionally when moved by air currents. He remained devoted to this approach with his mobiles and veered from it only very rarely, and not far when he did.

In 1962, in a review in Arts Magazine of an exhibit of Calder’s work at Tate [PDF], George Rickey wrote: “The mobile, even if flexible, is two-dimensional, like a drawing on a rubber sheet. The sinuous tracery of each set of wires profiles may sit contrapuntally against the next, but flat against flat. With the parts swinging around a vertical axis, the galaxy occupies space but does not energize it. Calder has run through the permutations of these wire profiles; yet, apart from some perfecting of wire technology, extension and refinement of his vocabulary of shapes (the Arpesque flame forms are the best), and increased size, he shows very little advance in the expressive use of movement in the thirty years since Calderberry Bush [also known as Object with Red Discs, made in 1932 and regarded as Calder’s first mobile sculpture]. It is not the first time that an artist has been confined by his own invention; it happened to Samuel F. B. Morse. The Master of the Catenaries has become the prisoner of the chain he forged.“

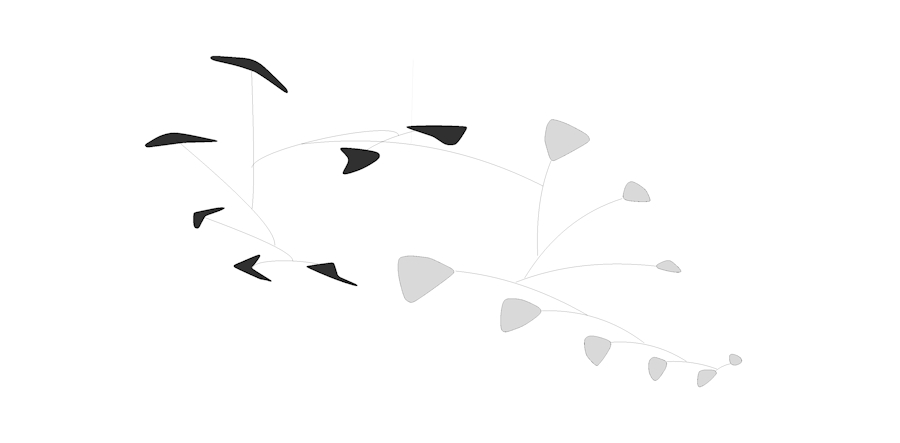

To expand Calder’s idea, one could create mobiles with the same balance structure as Calder’s mobiles (based on the whippletree mechanism), and create moving abstract “paintings” that are truly three-dimensional, not just two-dimensional planes made of a series of flat shapes that curve with the air currents.

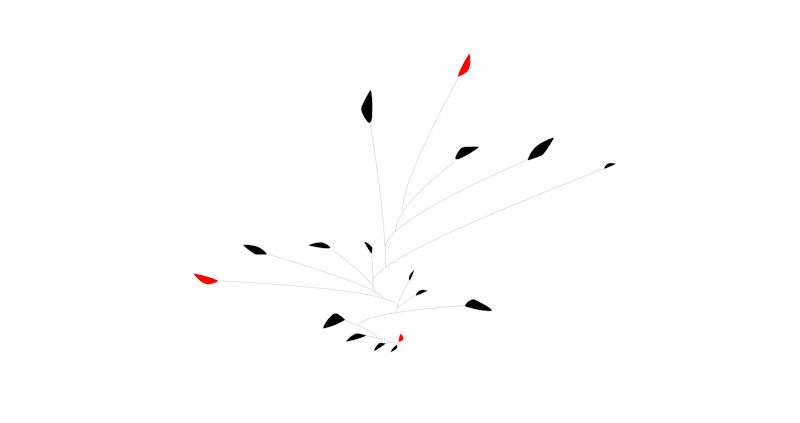

In his later years, Calder designed and made some of his mobiles consisting of two (or more) horizontal and vertical planes, each one being essentially arranged in two dimensions. His hanging mobile titled Lone Red Among Blacks (1961) is a good example to illustrate this. Here again, the three-dimensionality was a result of combining two or more “flat” two-dimensional arrangements, not of a fully three-dimensional arrangement.

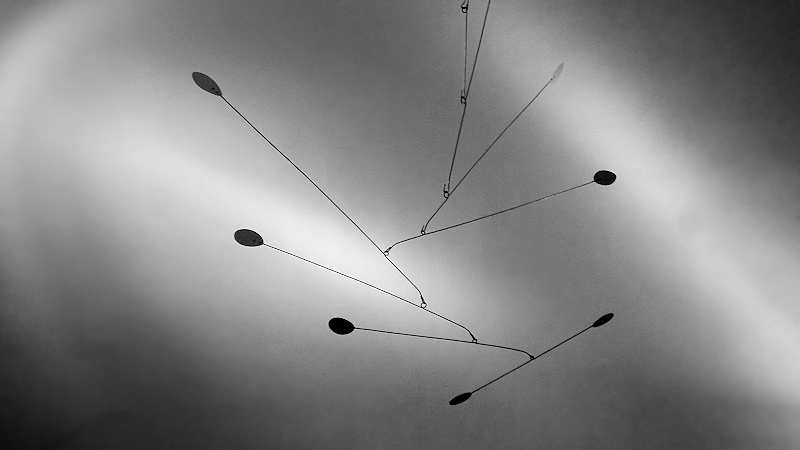

These mobiles shown here are still designed with the interconnected balance structure where the balance of each part depends on the other parts, as in a Calder mobile. And same as in Calder’s mobiles, it’s essentially an upside down whippletree mechanism, which probably dates back to between 190 to 209 AD, and has been used to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon:

Man Ray was the first artist (to my knowledge) to utilize this balance structure in a suspended sculpture with his piece titled Obstruction in 1920 (if you’d like to read more about the history of mobiles, please see my page Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles Part 1).

Almost all artists who have made mobiles since Calder have adapted his two-dimensional approach. Few have worked to move beyond and explore the possibilities of fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that utilize the interconnected balance structure that distinguishes them from simply suspended sculptures (please see my page Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles – Part 2 for some examples). George Rickey recognized the limitations of Calder’s two-dimensional approach to mobiles and expanded the art form, although many of his pieces don’t utilize an interconnected balance structure throughout. After around 1950, he often also opted for standing sculptures instead of suspended ones. Lynn Chadwick, Tim Prentice, Jerome Kirk, Derick Pobell, Laurent Martin “Lo”, Philippe Jestin and Jade Oakley have found ways to some extend to free the art form of mobiles from Calder’s two-dimensional approach. Tim Prentice expressed the challenge in a conversation with Nicholas Fox Weber (published by Maxwell Davidson Gallery in 2000): “Calder was credited with inventing sculpture with moving parts, so for me Rickey was incredibly important because he demonstrated that this concept wasn’t any one man’s property. I can do it to a limited degree. I can draw a line and have it curve, undulate, curl, turn, twist – in that sense, the line is changing – and I can do it with planes. The next challenge would be to do it with volume.” Volume as in three-dimensional planes instead of two-dimensional planes? Or no planes at all?

On the topic of Calder and Rickey, Tim Prentice wrote in his book Drawing on the Air – The Kinetic Sculptures of Tim Prentice: “If you compare the two, Calder was a great storyteller [and an entertainer] and not a theorist. When anyone asked him tough questions about his work, he hid behind his humor. For example, when asked how he knew a piece was finished, he famously answered, “When it’s dinner time.” He operated entirely on intuition. By contrast, Rickey was an intellectual and teacher. He was far more strict in his use of Constructivist principles. He analytically isolated movement in the way Josef Albers isolated color. [Rickey] and Calder represent the two contrasting sides of the brain.” Tim Prentice’s work greatly expands the art form of mobiles. He seems to build on Rickey’s approach more than on Calder’s. As he himself has explained: “As I concentrated on reducing weight and friction, the decisions came to be based more on engineering and less on aesthetics” and “we make the machine and keep our artistic instincts out of it and the air comes along and does the art.” Can the contrasting approaches be combined in new ways?

Building on Calder’s hanging mobile 13 Spines (1940):

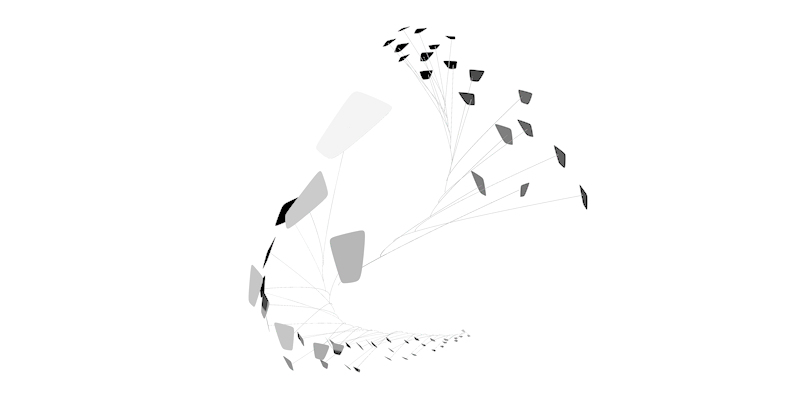

Photos reverse the idea of turning an abstract painting or drawing into a three-dimensional moving sculpture. They turn it back into a flat immobile image made of abstract shapes. Two-dimensional layouts in mobiles, like many of Calder’s mobiles and the more conventional mobile sculptures I made some years ago, are easier to capture and comprehend in photos. While video can provide a solution to this, most people discover new art in the form of photos nowadays, especially now in the digital age. You can make an amazing three-dimensional sculpture, but if the sculpture doesn’t allow you to represent its idea comprehensively in images and photos, then you’re limiting the reach of the idea greatly. As Sarah Sze put it in an interview with Melissa Chiu: “In many ways, great artworks are known primarily through photos – so arguably the photos are as important as the artworks themselves.”

An approach that seems architectural to me:

The balance structure of a mobile (the whippletree mechanism) is like a few simple chords on an instrument: simple, but the possibilities of what can be done with it are infinite.

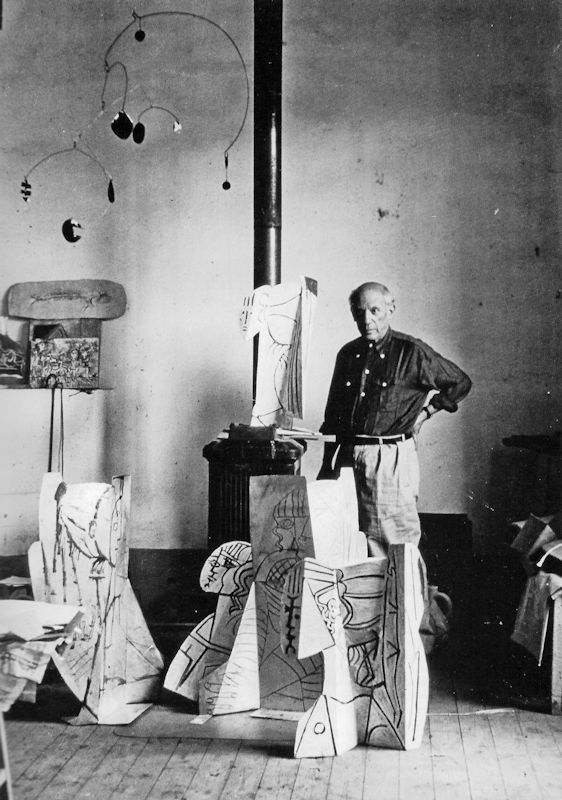

“Paintings are but research and experiment. I never do a painting as a work of art. All of them are researches.” – Pablo Picasso, in an interview with Alexander Liberman for Vogue in 1956.

Or as architect Santiago Calatrava has pointed out: the surrealist André Breton said, “Everyone knows what a head looks like”, to which Alberto Giacometti retorted: “Not me.”

See the continuation of this post Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form – Part 2 with additional new mobile sculptures that I’m working on based on this approach.

As with anything on my website, if you have any suggestions, anything that should be added, corrected, or have any questions or comments, please let me know.

– See more of my mobiles –

Where’s the Line between a Calder Replica and a Calder Inspired Mobile?

Every now and then I receive a request from a client to make a custom-designed Calderesque mobile, a mobile in the style of Alexander Calder, inventor of modern mobiles. I am not allowed, nor is anyone else, to make replicas (exact reproductions) of his mobiles. They are protected by copyright. I would refer you here to Manuel Marin (1942–2007) who was an artist and a convicted art forger. He admitted to making and selling millions of dollars of forgeries, mainly copies of works by Calder, and served prison sentences for his crimes.

Yet when I draw up proposals for these kinds of projects, I keep wondering where the lines are between a mobile that could be a replica, a mobile that’s strongly influenced by Calder’s style (“in the manner of Alexander Calder”), and a Calder inspired mobile. If I copied his style to a tee, most people wouldn’t be able to tell it from an original Calder mobile, yet it wouldn’t be a replica.

The question here is not simply about style, because Calder invented a new art form, and he still is to date by very far the most well known sculptor to create mobiles. This could be compared to Wassily Kandinsky, who is often (arguably) noted as having created the first abstract paintings starting in 1911, and then attributing all abstract paintings that followed by others to his work. An important difference here being that compared to abstract painting, few kinetic sculptors have tried to create their own style of mobiles so far, and even then, the basic idea, and in many cases the structures of their mobiles, are based on Calder’s work, and in that way, most mobiles are Calder inspired, even if they’re original in style. However, the underlying idea and structure of Calder’s mobiles was not invented by Calder. It is based on Man Ray‘s 1920 piece titled Obstruction, which he made about 10 years before Calder started to make mobiles. It utilizes the same structure as a whippletree mechanism, which probably dates back to between 190 to 209 AD. For further reading on this topic, please see the photos below of Calder’s copy of Man Ray’s sculpture, and see my page Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles.

From a legal perspective, case law is telling us that style isn’t protected by copyright. In Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures, the court stated that style is merely one ingredient of expression and for there to be infringement, there has to be substantial similarity between the original work and the new, purportedly infringing, work. In Dave Grossman Designs v. Bortin, the court said that:

“The law of copyright is clear that only specific expressions of an idea may be copyrighted, that other parties may copy that idea, but that other parties may not copy that specific expression of the idea or portions thereof. For example, Picasso may be entitled to a copyright on his portrait of three women painted in his Cubist motif. Any artist, however, may paint a picture of any subject in the Cubist motif, including a portrait of three women, and not violate Picasso’s copyright so long as the second artist does not substantially copy Picasso’s specific expression of his idea.”

For more on the legal perspective, there’s a great article by Greg Kanaan titled You Can’t Copyright Style.

The sculptor Jerome Kirk, who in his early career was strongly influenced by Calder, went to visit him at his studio around 1954, and described the encounter in his book: “Low on money and feeling the need for some encouragement, I visited Alexander Calder at his home in Roxbury, Connecticut. To enter his studio was like walking into a dream world. There were large work benches, vices, anvils and a magnificent clutter of tools, wire and sheet metal. His mobiles and stabiles of varying sizes were everywhere. At first Calder seemed interested in wanting to know what I was all about, but his cordiality gave way to petulance after seeing examples of my work. Guessing that he resented the close resemblance of my work to his own, I left discouraged, saddened and angry.” Jerome Kirk went on to creating his own very original style with his kinetic sculptures.

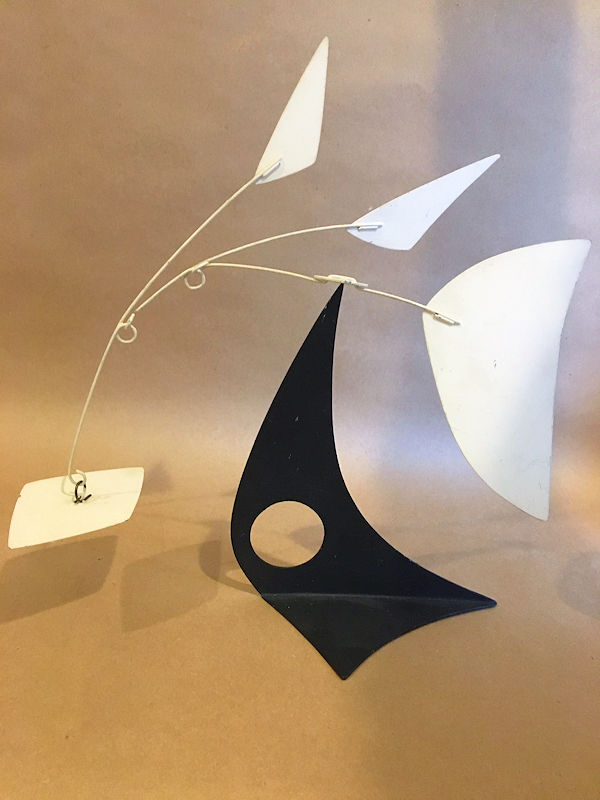

A standing mobile by Arthur Bauman:

A standing mobile by Calder (Quatre Blancs, 1976):

Pablo Picasso once said: “What does it mean for a painter to paint in the manner of So-and-So or to actually imitate someone else? What’s wrong with that? On the contrary, it’s a good idea. You should constantly try to paint like someone else. But the thing is, you can’t! You would like to. You try. But it turns out to be a botch. And it’s at the very moment that you make a botch of it that you’re yourself.” (Hélène Parmelin, Picasso: The Artist and His Model, and other recent Works, 1965, page 43)

Picasso in his studio in 1956 standing next to a mobile not made by Calder:

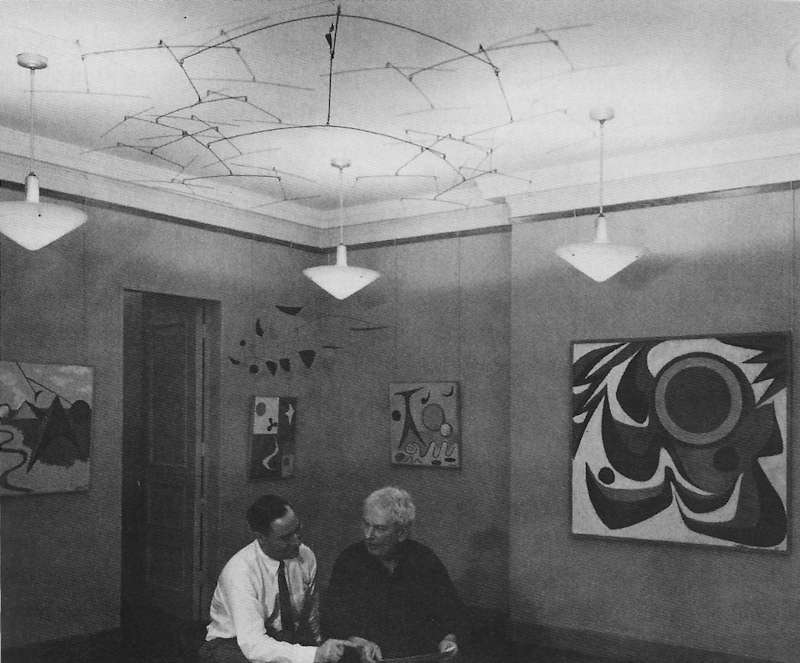

Here’s Calder (with Klaus Perls) at Calder’s 1956 exhibit at Perls Galleries with a copy (Untitled – Mobile with N Degrees of Freedom) that he made in 1946 of Man Ray’s sculpture titled Obstruction from 1920 suspended from the ceiling. It’s essentially the same sculpture just made with wire instead of coat hangers:

Man Ray’s Obstruction that he made in 1920:

On the topic of style, as in style in fine art and art movements, Calder is widely regarded as one of America’s most important surrealists, although he did not consider himself an abstract artist, as noted by Milly Burroughs. When pressed on this matter in an interview, Calder explained that his penchant for kinetic art and other-worldly forms was his interpretation of what the universe might look like, and would therefore be Realism.

– Read more of my blog posts about mobiles or see some of my mobile sculptures –

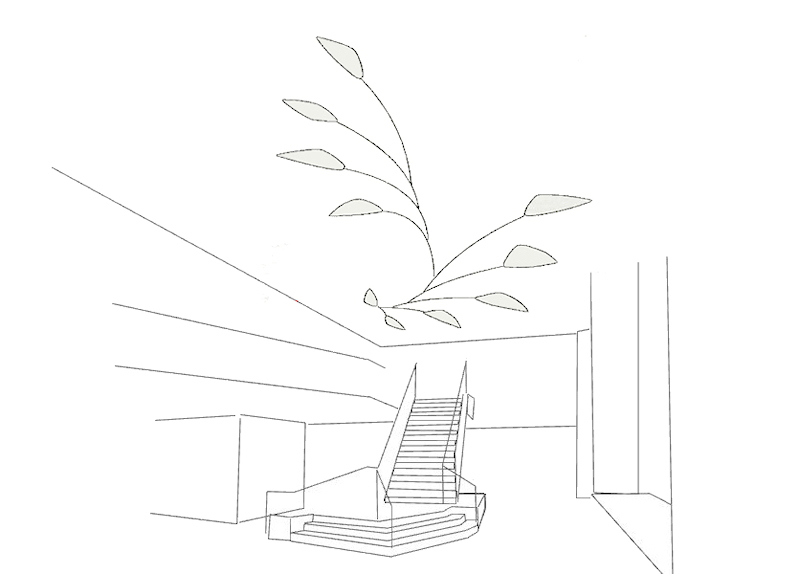

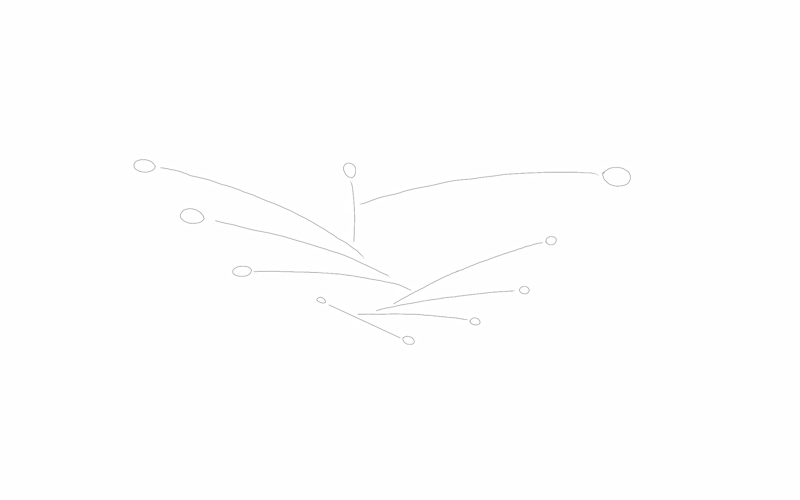

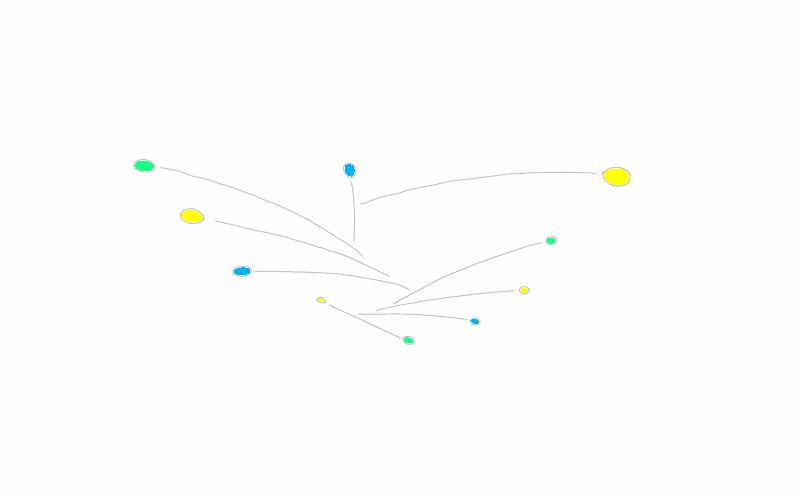

Butterfly themed large custom mobiles – early drafts

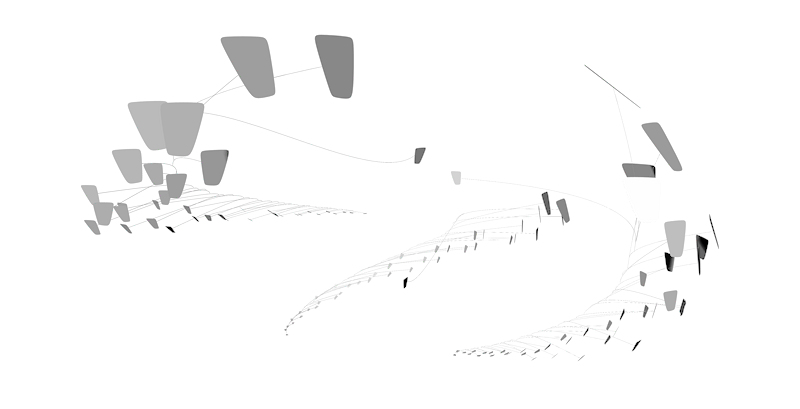

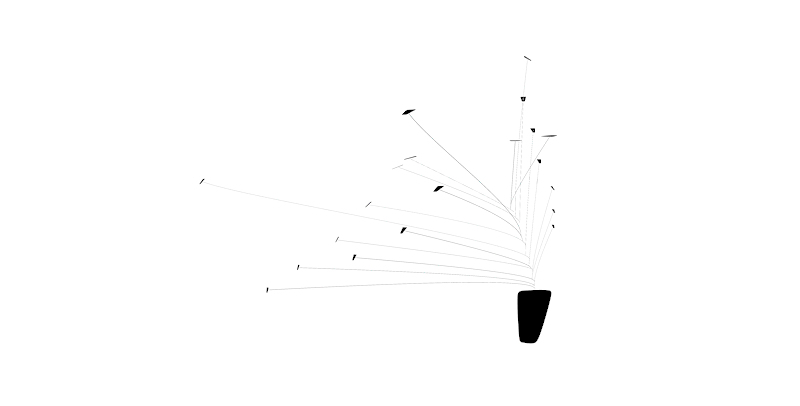

Designs I’m currently working on for large custom mobiles for a large staircase at a restaurant / theater being built on the Las Vegas strip – early drafts:

Designed with python scripts and rendered in Rhino.

Mixing contemporary art with movement, Calder style mobiles with 21st century design elements.

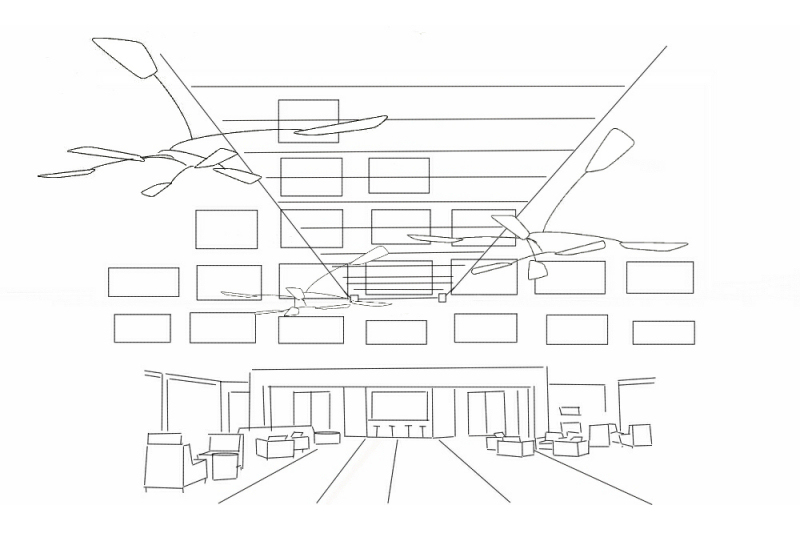

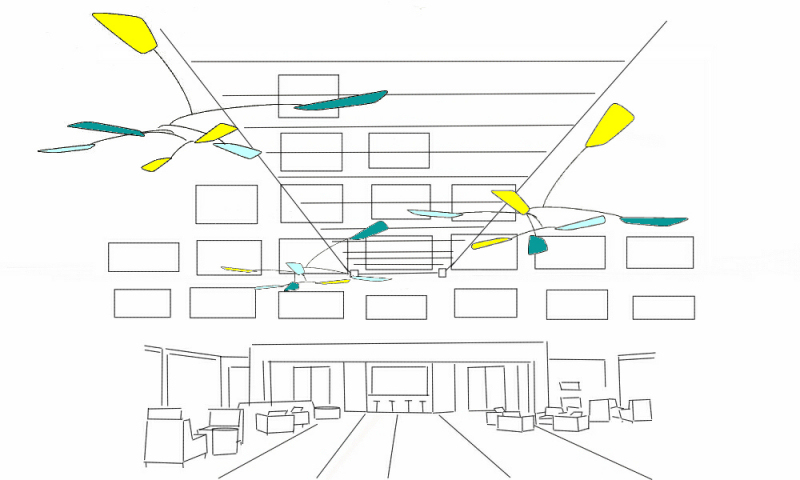

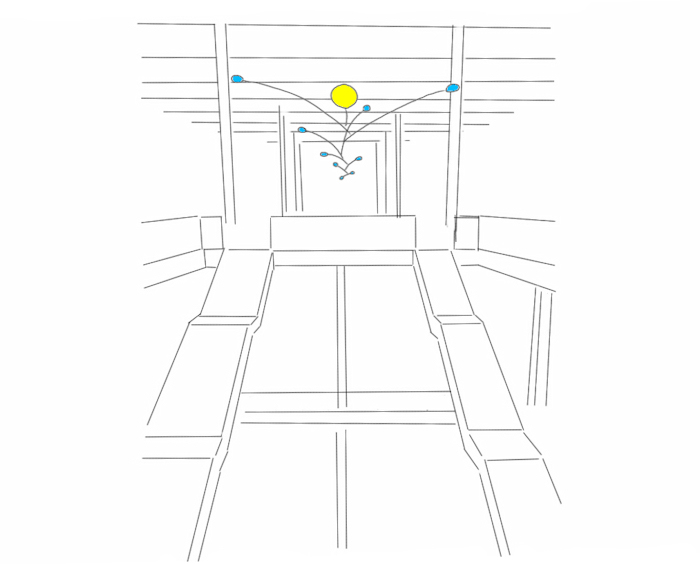

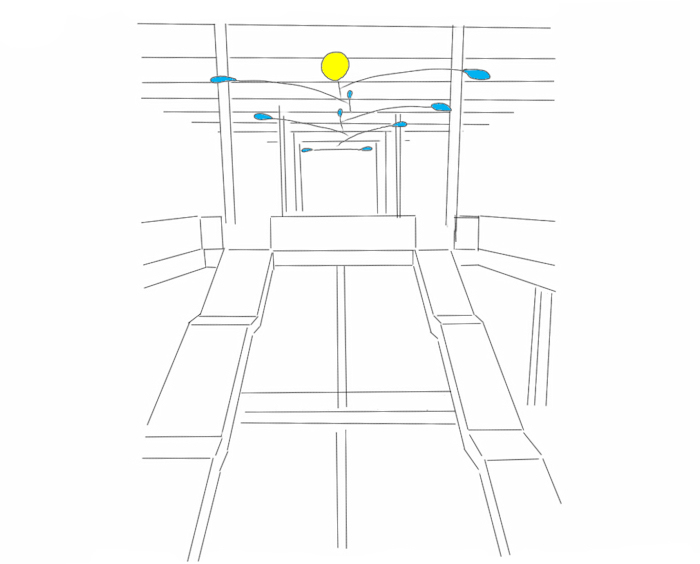

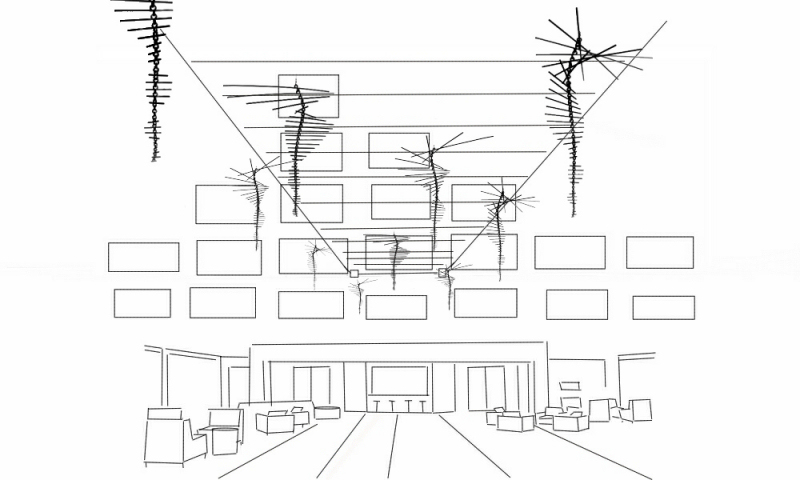

Designs for large custom-made mobiles for a hotel lobby

Design for three large custom-made hanging mobiles for a hotel lobby, based on a custom mobile I made for a private residence at the Butterfield House:

One more time with some colors:

And a second idea using a design from our 3D Printed Hanging Sculptures:

[Update: See the finished mobiles installed at the atrium]

See more of my custom-designed and custom-made mobiles …

Designs for large custom mobiles for a shopping mall – Part 1 – Smaller Atrium

Designs / sketches of two large custom hanging mobiles for a shopping mall in Kazakhstan:

See more of my custom mobiles …

What is the largest kinetic sculpture / mobile in the world?

There’s an amazing kinetic sculpture titled Kinetic Rain at Changi Airport designed by the highly creative and innovative ART + COM and manufactured and installed by MKT, Olching:

Links to various videos of the installation keep floating around social media sites calling it “the largest kinetic sculpture in the world”, spanning an area of 75 square meters (810 sq ft) and a height of 7.3 meters (24 ft). While the sculpture is an amazing accomplishment, it doesn’t seem to be the world’s largest kinetic sculpture. To my knowledge, the largest kinetic sculpture in the world (and also the largest mobile sculpture) is Alexander Calder‘s White Cascade, which hangs in the Eastburn Court of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia:

It measures approximately 100 feet (31 meters) from top to bottom, is 60 feet (18 meters) at its widest point, and weighs close to 10 tons, including the motor, surpassing Calder’s 920 pound 76-foot-long mobile (or 85 feet, depending on source) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. I’m not sure if any of his stabiles are larger, but if not, then this would also be Alexander Calder’s largest sculpture. Speaking of that large Calder mobile at the National Gallery, it is made with hollow honeycomb-type structures designed by Paul Matisse (grandson of Henri Matisse and son of Pierre Matisse) and covered with paper-thin aluminum, and aluminum and steel bars, with the stress points being strengthened with molybdenum. It weighs 930 pounds (422 kg). The previous estimates from Calder’s foundry in Biémont exceeded 5000 pounds (2268 kg). It doesn’t have a name. When Calder was asked for a title, he replied “You don’t name a baby until it is born.” But then he passed away one year before it was installed at the Gallery. The mobile sculpture has been refurbished recently.

Back to White Cascade: It took just two days to install it. The installation was carried out in two stages. In the most difficult and time-consuming part of the job, the four top-most and largest aluminum discs — still in their protective wrappings — were joined to their respective stainless steel rods, then raised one by one and linked together. The 10 lower discs and rods were linked together on the ground level, then raised into position as a unit. A crane situated on the sidewalk outside the entrance to the Bank provided the lifting power.

Finally, the wrappings were removed. The 14 white aluminum discs that comprise “White Cascade” range in size from 3.5 feet in diameter to 12.7 feet. The longest of the connecting stainless steel rods is 36 feet; the shortest, 9 feet. Powered by an electric motor, the mobile rotates clockwise on a radius of 32.5 feet.

Here’s a photo by H. Scott Heist of Calder in front of the mobile:

The mobile was installed in May 1976, Calder passed away less than six months later.

Do you know of a larger kinetic sculpture? Let me know if you do and I’ll add it to this post.

Also see my list of the 5 Largest Mobiles worldwide that I’m aware of.

– Update: –

I received an email from Anthony Howe nominating his OCTO 3 sculpture as possibly the largest outdoor permanent kinetic wind sculpture. It measures 25′ h x 30′ w x 30′ d (7.6m x 9.1m x 9.1m) and weighs 7000 pounds (3200 kg):

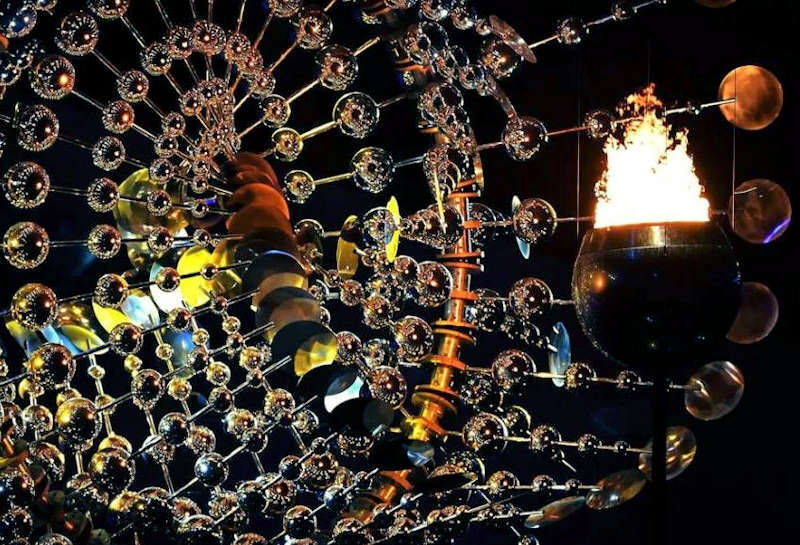

Since receiving the email from Anthony, it seems that he has surpassed these dimensions with the cauldron he created for the 2016 Rio Olympics measuring 40 ft (12.2 meters):

Related: Watch as Anthony Howe creates a massive, kinetic wind sculpture

– See some of my kinetic sculptures and mobiles –

Iconic 1960 Calder mobile from private collection on offer

Alexander Calder, Maripose, 1960, 30 x 67in.

Bonhams will offer Alexander Calder‘s (1898-1976) 1960 sculpture Maripose in the November 12 2013 Contemporary Art auction (est. $1,200,000-1,600,000). This stunning example of Calder’s large scale mobiles has been in private American hands for nearly 40 years in Wisconsin-based collections.

A native of Pennsylvania, Calder was born into a family of sculptors. His first solo show was held in Paris in 1927 while he was still in his twenties; he would soon become one of America’s most lauded and prolific artists. It was Marcel Duchamp who first dubbed Calder’s kinetic wire sculptures “mobiles,” – these hanging, interactive pieces would come to define the artist’s legacy.

Maripose was originally offered at Perls Gallery in New York, which represented Calder from 1954 until the artist’s death. The mobile was acquired in 1976 by a prominent private collector from Milwaukee’s Irving Galleries, and passed by descent to the present owner in 1988. The mobile was exhibited at the Milwaukee Art Museum in 1987, and is registered with the Calder Foundation.

“In Maripose, every element of Calder’s genius is evident through the striking sense of balance and momentum the sculpture evokes,” said Jeremy Goldsmith, Bonhams Director of Contemporary Art in New York. “It’s a pleasure to bring such an important work to the market after nearly four decades in private hands.”

The auction will preview at Bonhams November 9-12 2013.

Designs for a custom mobile for a private residence in Cape Cod

Designs / sketches for a custom hanging mobile for a private residence in Cape Cod

Alexander Calder and Fausto Melotti – London – October 11th – November 30th 2013

Ronchini Gallery is presenting a new exhibition titled “Calder & Melotti: Children of the Sky“, from October 11th – November 30th 2013, in collaboration with Museo Carandente Palazzo Collicola, Spoleto, Italy, curated by Director Gianluca Marziani. The exhibition features works by American artist Alexander Calder (1898-1976) and his Italian contemporary, Fausto Melotti (1901-1986). It tells the stories of two artists who took inspiration from the city of Spoleto and Italian cultural life in the post-War period.

This scholarly exhibition – including loans from private European collections and Museo Carandente Palazzo Collicola – is a rare opportunity to view many works which have never been publicly exhibited in the UK. While these artists were separated geographically, their respective bodies of work share many technical and aesthetic sympathies. Both artists employed a lyrical expressiveness in the often stolid medium of constructed metal sculpture. Influenced by both the Surrealists and Constructivists, Calder and Melotti were each attracted to working with iron and malleable alloys, using these materials to represent the balance of opposing forces. Both men were trained in engineering before turning to art and were interested in music and dance. Melotti trained as a pianist and often discussed his works in musical terms. Calder often collaborated with composers and choreographers. In their works, the precision of the engineer combines with a musician’s sense of rhythm, balance and play.