Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form

What I’m currently (2024) working on in my apparently perpetual endeavor to expand the art form of mobiles beyond the limitations of Alexander Calder‘s work: Calder described his approach to designing and making his mobiles in a conversation with Selden Rodman in 1957: “I used to begin with fairly complete drawings, but now I start by cutting out a lot of shapes. Next, I file them and smooth them off. Some I keep because they’re pleasing or dynamic. Some are bits I just happen to find. Then I arrange them, like papier collé, on a table, and “paint” them – that is, arrange them, with wires between the pieces if it’s to be a mobile, for the overall pattern.” His mobiles become three-dimensional when suspended as each part moves and rotates with the air currents. But his approach to the layout of a mobile is essentially two-dimensional, on a table. Calder’s Vertical Foliage is good example to illustrate this. However, there seems to be creative approaches to fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that Calder only very rarely ventured into (his mobile Red Cascade made in 1960 is an example). Here are some of the ideas and experiments that I’m currently working on and experimenting with, finding ways to expand his approach (and there’s also a continuation of this post Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form – Part 2):

George Rickey, while outlining the early explorations by artists into kinetic art from 1912 to 1932 in his book Constructivism – Origins and Evolution (published in 1967, and to my knowledge, the most wide-ranging and comprehensive book on the subject of Constructivism to date), remarked: “It was Calder who succeeded in securing a place for kinetic art. He started making mobiles twelve years after Gabo’s Manifesto, and his first exhibition of these was in 1932 at the Galérie Maeght in Paris. Although his mobiles have since become famous and popular and have enlarged the limits of art, his style, deriving from painterly concepts, has had little influence on the new generation, especially the more mechanically inclined. Until his stabiles of the last decade, Calder retained a two-dimensional outlook in sculpture devised as outline drawings, often witty, with ingratiating movement added. He seemed indifferent to the wide possibilities of a kinetic art. He discovered a new world but did not explore it.“

To put the idea in different words: Calder’s process began with seeing Piet Mondrian‘s paintings and feeling the impulse to make the static abstract shapes in the paintings move. He translated this idea to his mobiles quite precisely, essentially creating two-dimensional abstract paintings made of a series of flat shapes that move. Most of them only happen to become three-dimensional because these two-dimensional abstract “paintings” (essentially two-dimensional planes made of a series of flat shapes) happen to curve three-dimensionally when moved by air currents. He remained devoted to this approach with his mobiles and veered from it only very rarely, and not far when he did.

In 1962, in a review in Arts Magazine of an exhibit of Calder’s work at Tate [PDF], George Rickey wrote: “The mobile, even if flexible, is two-dimensional, like a drawing on a rubber sheet. The sinuous tracery of each set of wires profiles may sit contrapuntally against the next, but flat against flat. With the parts swinging around a vertical axis, the galaxy occupies space but does not energize it. Calder has run through the permutations of these wire profiles; yet, apart from some perfecting of wire technology, extension and refinement of his vocabulary of shapes (the Arpesque flame forms are the best), and increased size, he shows very little advance in the expressive use of movement in the thirty years since Calderberry Bush [also known as Object with Red Discs, made in 1932 and regarded as Calder’s first mobile sculpture]. It is not the first time that an artist has been confined by his own invention; it happened to Samuel F. B. Morse. The Master of the Catenaries has become the prisoner of the chain he forged.“

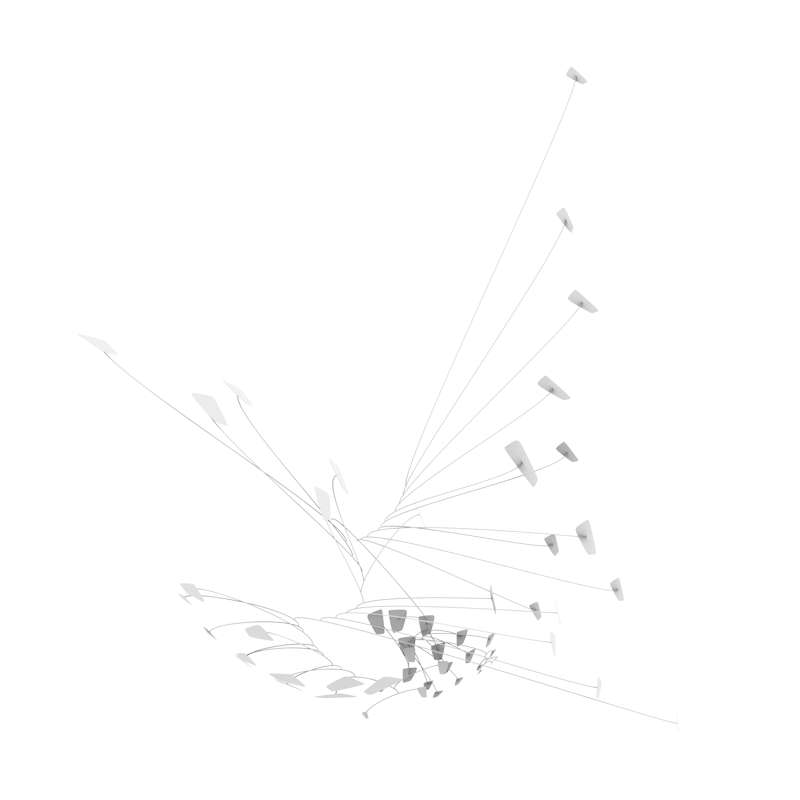

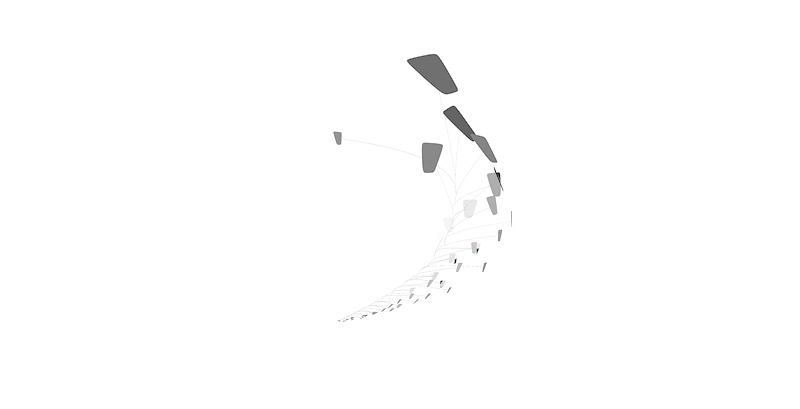

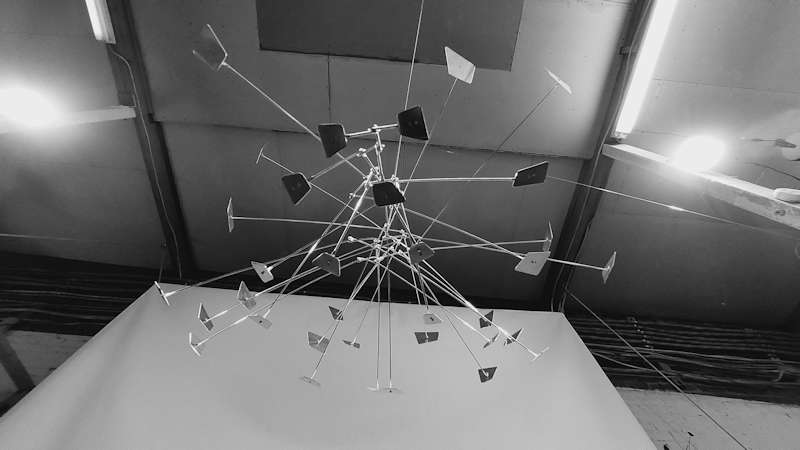

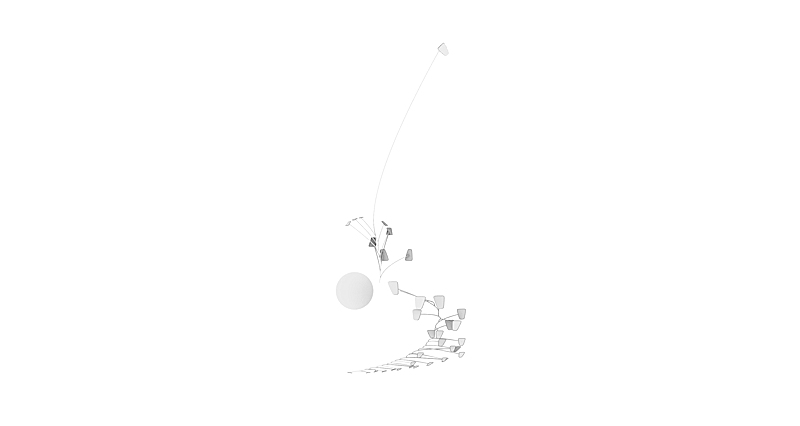

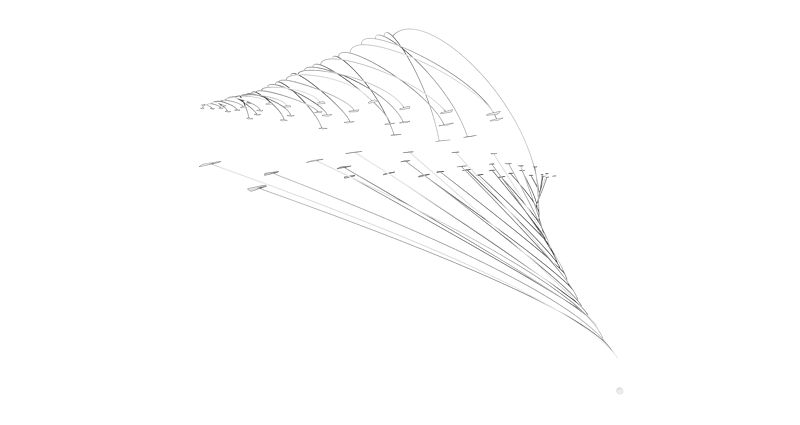

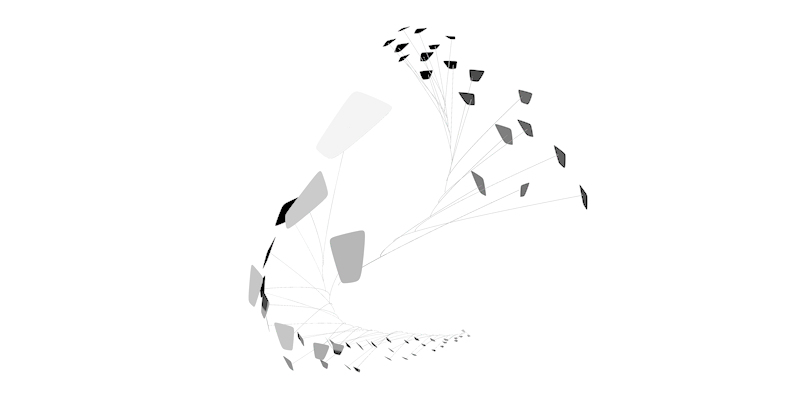

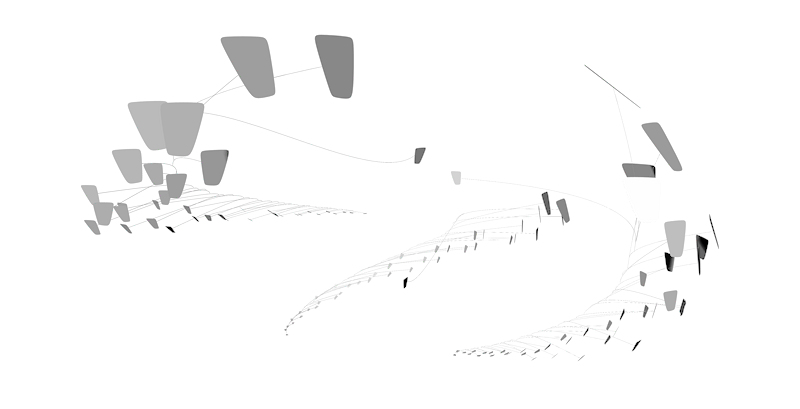

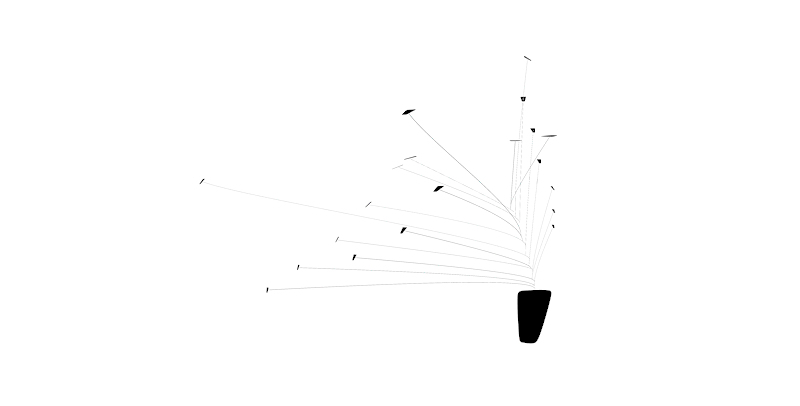

To expand Calder’s idea, one could create mobiles with the same balance structure as Calder’s mobiles (based on the whippletree mechanism), and create moving abstract “paintings” that are truly three-dimensional, not just two-dimensional planes made of a series of flat shapes that curve with the air currents.

In his later years, Calder designed and made some of his mobiles consisting of two (or more) horizontal and vertical planes, each one being essentially arranged in two dimensions. His hanging mobile titled Lone Red Among Blacks (1961) is a good example to illustrate this. Here again, the three-dimensionality was a result of combining two or more “flat” two-dimensional arrangements, not of a fully three-dimensional arrangement.

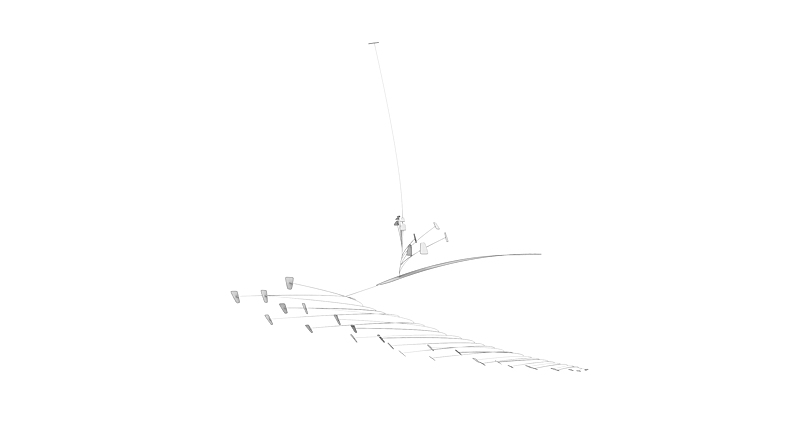

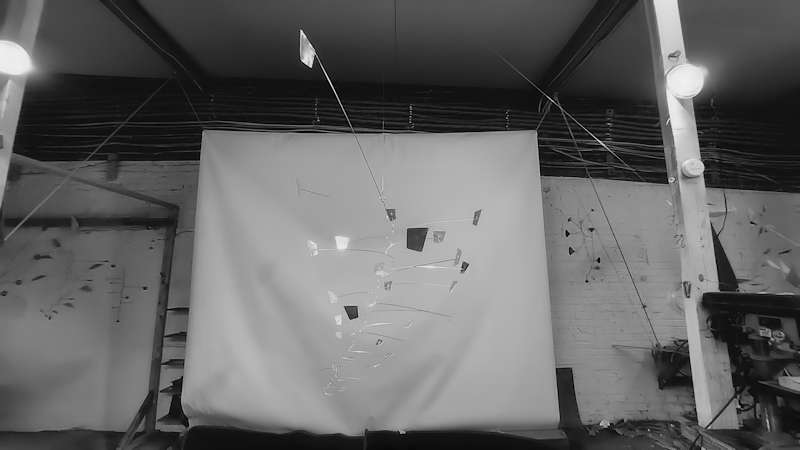

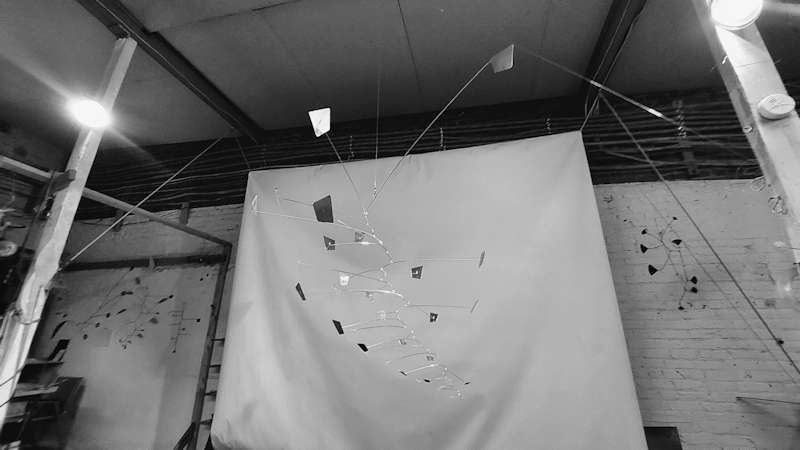

These mobiles shown here are still designed with the interconnected balance structure where the balance of each part depends on the other parts, as in a Calder mobile. And same as in Calder’s mobiles, it’s essentially an upside down whippletree mechanism, which probably dates back to between 190 to 209 AD, and has been used to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon:

Man Ray was the first artist (to my knowledge) to utilize this balance structure in a suspended sculpture with his piece titled Obstruction in 1920 (if you’d like to read more about the history of mobiles, please see my page Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles Part 1).

Almost all artists who have made mobiles since Calder have adapted his two-dimensional approach. Few have worked to move beyond and explore the possibilities of fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that utilize the interconnected balance structure that distinguishes them from simply suspended sculptures (please see my page Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles – Part 2 for some examples). George Rickey recognized the limitations of Calder’s two-dimensional approach to mobiles and expanded the art form, although many of his pieces don’t utilize an interconnected balance structure throughout. After around 1950, he often also opted for standing sculptures instead of suspended ones. Lynn Chadwick, Tim Prentice, Jerome Kirk, Derick Pobell, Laurent Martin “Lo”, Philippe Jestin and Jade Oakley have found ways to some extend to free the art form of mobiles from Calder’s two-dimensional approach. Tim Prentice expressed the challenge in a conversation with Nicholas Fox Weber (published by Maxwell Davidson Gallery in 2000): “Calder was credited with inventing sculpture with moving parts, so for me Rickey was incredibly important because he demonstrated that this concept wasn’t any one man’s property. I can do it to a limited degree. I can draw a line and have it curve, undulate, curl, turn, twist – in that sense, the line is changing – and I can do it with planes. The next challenge would be to do it with volume.” Volume as in three-dimensional planes instead of two-dimensional planes? Or no planes at all?

On the topic of Calder and Rickey, Tim Prentice wrote in his book Drawing on the Air – The Kinetic Sculptures of Tim Prentice: “If you compare the two, Calder was a great storyteller [and an entertainer] and not a theorist. When anyone asked him tough questions about his work, he hid behind his humor. For example, when asked how he knew a piece was finished, he famously answered, “When it’s dinner time.” He operated entirely on intuition. By contrast, Rickey was an intellectual and teacher. He was far more strict in his use of Constructivist principles. He analytically isolated movement in the way Josef Albers isolated color. [Rickey] and Calder represent the two contrasting sides of the brain.” Tim Prentice’s work greatly expands the art form of mobiles. He seems to build on Rickey’s approach more than on Calder’s. As he himself has explained: “As I concentrated on reducing weight and friction, the decisions came to be based more on engineering and less on aesthetics” and “we make the machine and keep our artistic instincts out of it and the air comes along and does the art.” Can the contrasting approaches be combined in new ways?

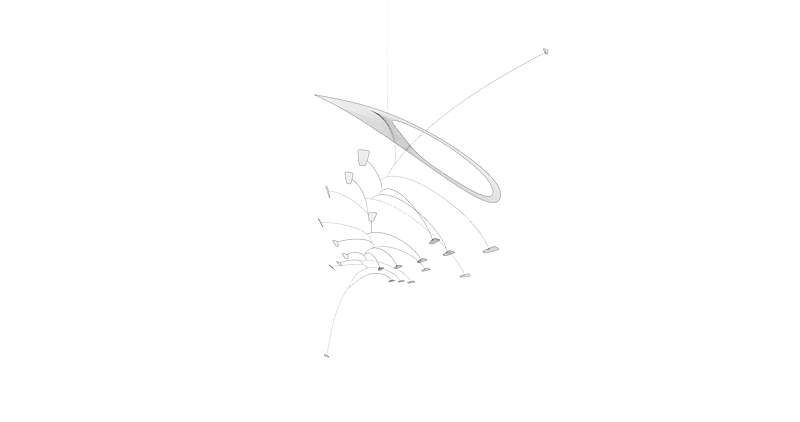

Building on Calder’s hanging mobile 13 Spines (1940):

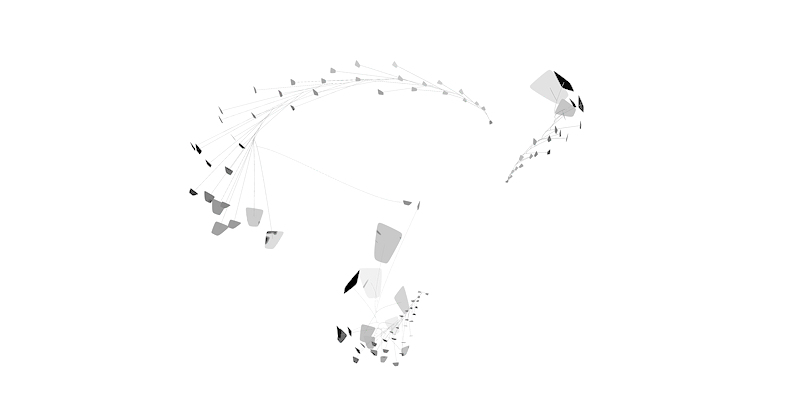

Photos reverse the idea of turning an abstract painting or drawing into a three-dimensional moving sculpture. They turn it back into a flat immobile image made of abstract shapes. Two-dimensional layouts in mobiles, like many of Calder’s mobiles and the more conventional mobile sculptures I made some years ago, are easier to capture and comprehend in photos. While video can provide a solution to this, most people discover new art in the form of photos nowadays, especially now in the digital age. You can make an amazing three-dimensional sculpture, but if the sculpture doesn’t allow you to represent its idea comprehensively in images and photos, then you’re limiting the reach of the idea greatly. As Sarah Sze put it in an interview with Melissa Chiu: “In many ways, great artworks are known primarily through photos – so arguably the photos are as important as the artworks themselves.”

An approach that seems architectural to me:

The balance structure of a mobile (the whippletree mechanism) is like a few simple chords on an instrument: simple, but the possibilities of what can be done with it are infinite.

“Paintings are but research and experiment. I never do a painting as a work of art. All of them are researches.” – Pablo Picasso, in an interview with Alexander Liberman for Vogue in 1956.

Or as architect Santiago Calatrava has pointed out: the surrealist André Breton said, “Everyone knows what a head looks like”, to which Alberto Giacometti retorted: “Not me.”

See the continuation of this post Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form – Part 2 with additional new mobile sculptures that I’m working on based on this approach.

As with anything on my website, if you have any suggestions, anything that should be added, corrected, or have any questions or comments, please let me know.

– See more of my mobiles –