How to Build / Make Mobiles / Kinetic Sculptures

I’m a kinetic sculptor specializing in mobiles. I’ve received e-mails over the years asking to know how to make mobiles, which eventually prompted me to put together this page. It explains the basics about the balance structure that a mobile is made of, which is essentially a whippletree mechanism. It’s all about physics, which may seem complicated at first, but it’s actually really quite simple if you build the structure from the bottom to the top of the mobiles, just like Alexander Calder (who invented the art form of mobiles in the early 1930s) did. Look through the following four illustrations, then read the rest below.

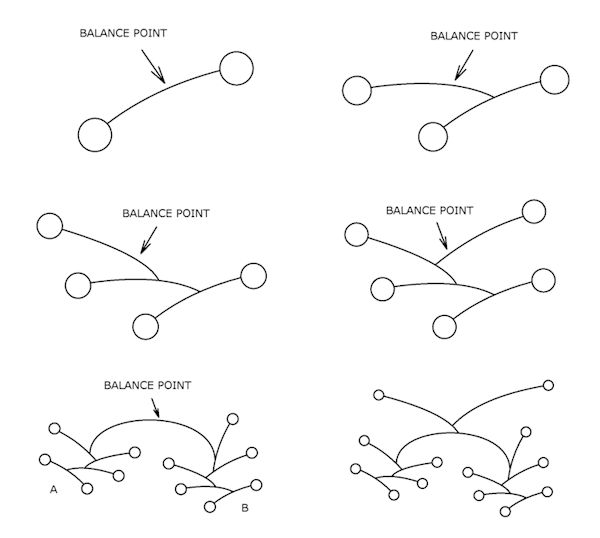

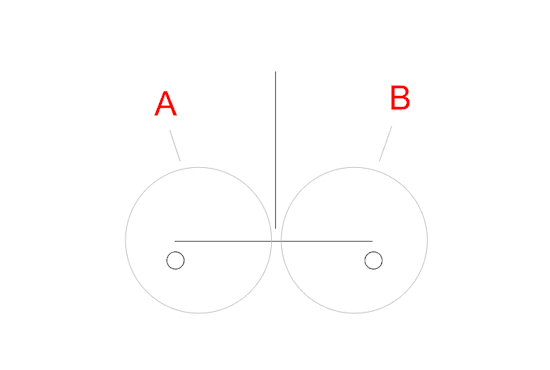

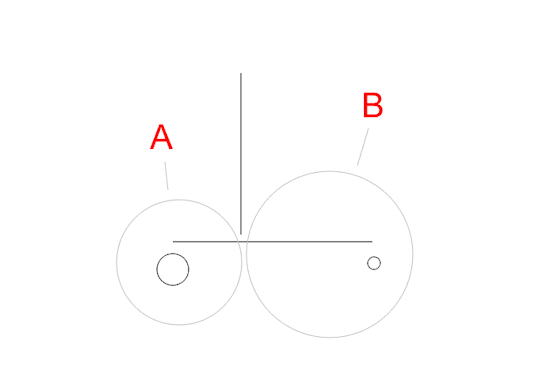

Part A weighs the same as part B – Balance point is right in the middle:

Part A weighs more than part B – Balance point moves closer to part A, the heavier part:

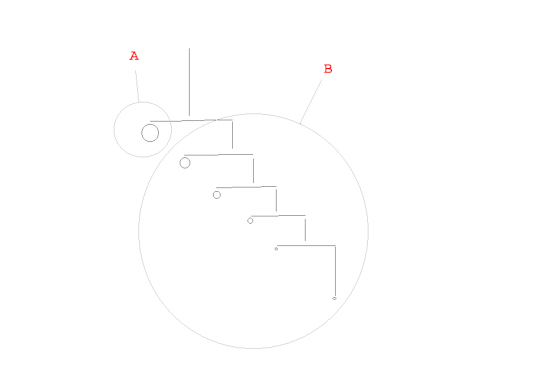

The following illustration might look more complex, but it’s really the exact same idea. All those lower parts marked as “B” count as just one part when it comes to the balance of the top part, it’s still only about the balance between part A and part B:

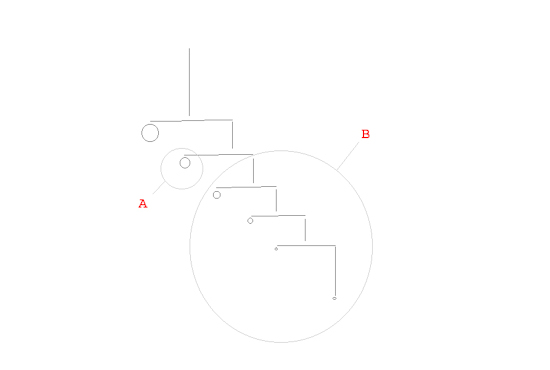

And then it just goes on like that to the next level of the mobile:

The trick is that you build the mobile from bottom to top. Start with connecting the first two elements at the bottom of the mobile and find the balance point between them. Then you connect the next upper element to that balance point, and again, find the balance point between the new element and the first two elements and so on. You can find the balance point by holding the connecting arm with your fingers and moving it back and forth, or if you want to be exact, tie a string around the connecting arm and move it back and forth until it balances.

In Alexander Calder’s own words: “I begin with the smallest and work up. Once I know the balance point for this first pair of discs, I anchor it by a hook to another arm, where it acts as one end of another pair of scales, and so on up. It’s a kind of ascending scale of weights and counterweights.” – from Curtis Cate, Calder Made Easy, Horizon Magazine, vol. 9, no. 1 (Winter 1972).

I would also recommend to take a look at a how-to article I wrote for Houzz: From the Artist: How to Make a Real Mobile

Once you understand the basics on how to build this balance structure, anything goes from there. You can use whatever you like for the weights at the end of the arms, and you can play around with how you build the structure, make some arms longer than others, make some of them point in a more vertical direction than others, and so on. The possibilities are infinite.

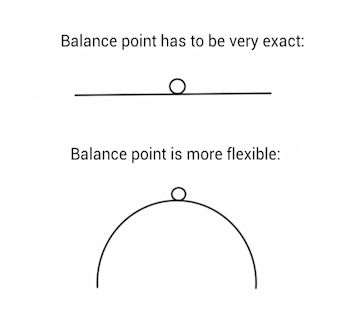

Oh, here’s something else to consider:

There’s no need to understand this beyond what the above illustration shows, but if you’re interested in physics: there’s a balance point and a center of the mass (weight) for an object. If the center of mass of the object is above the balance point (meaning the majority of the weight is above the balance point), the object will fall over. If the center of mass of the object is below the balance point, it will balance. The farther below the balance point the center of mass is, the more stable is the balance. So by making the parts of a mobile curved downwards, you lower the center of mass, and therefore making it more stable and easier to balance. Also see my blog post Balance – Suspension Points and the Centers of Mass in Abstract Mobile Sculptures and there’s also a Wikipedia page about the center of mass that explains more about this.

You can also use “sliders” to build flexibility into your mobile designs. Using sliders to adjust the balance points on a mobile allows for easy experimentation with design options and reduces the chance of wasted materials. Also take a look at the micro-adjustment sliders that Jay Jones developed for his line of “Build it Yourself” Mobile Kits. He tested over 30 materials and configurations before arriving at the one used. The kits are also available at MoMA NYC, MoMA SF, Guggenheim NYC and the Smithsonian among other museum shops. It appears that Jay Jones has stopped making them in 2020 or 2021, so they may be sold out in some shops now.

Additional resources for making mobiles:

- Blog post I wrote about What Wire to Use to Make a Hanging Mobile and Where to Buy It

- Blog post with mobile-making related questions that I’ve received via email and my answers

- An article I wrote for MAKE magazine on How to Make a Mobile Based on Calder’s Mobiles

- An article I wrote for Houzz: From the Artist: How to Make a Real Mobile – It’s All in the Balancing Points (there’s a number of questions and answers in the comment section of the article as well). The article is now also available in German

- A history of early mobiles that I’ve put together

- Some technical (“behind-the-scenes”) aspects of designing, making and installing a large custom mobile

- A definition of mobiles

- Q&A about Mobiles for a middle school student’s math class project

- See some of my mobiles if you’re looking for design ideas: handmade mobiles, large custom-made mobiles, 3D printed mobiles and kinetic sculptures

If there’s anything else I can help with, don’t hesitate to contact me.

And just for fun, here’s another quote by Alexander Calder when he was asked how he gets that subtle balance in his work: “You put a disk here and then you put another disk that is a triangle at the other end and then you balance them on your finger and keep on adding. I don’t use rectangles––they stop. You can use them; I have at times but only when I want to block, to constipate movement.”

A diagram by Alexander Calder on how to install one of his mobiles at the IMA in 1947:

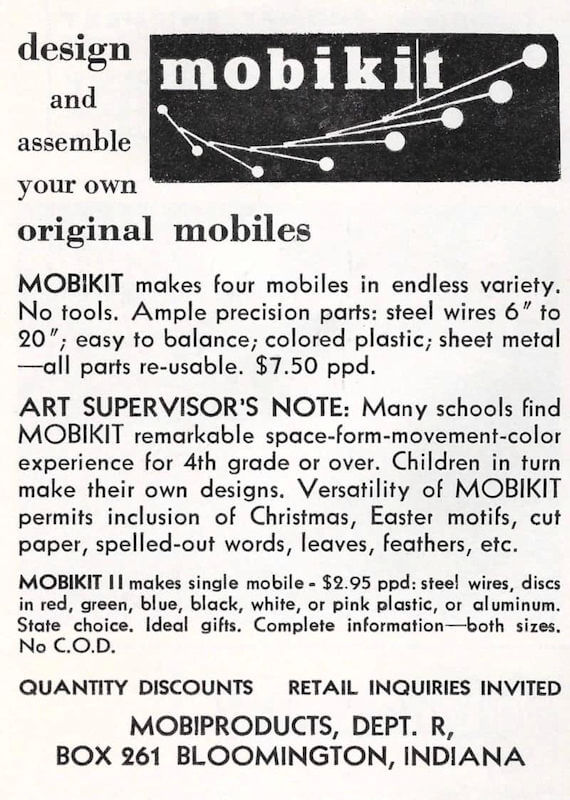

In 1952, George Rickey also invented a mobile making kit, the “Mobikit”, his first commercial project – via the George Rickey Foundation:

The kit included parts for making mobiles in endless variety. Alexander Calder’s work was wildly popular at the time, and Rickey’s Mobikit aimed to capitlize on the mobile craze. Rickey hoped the mobikit would appeal to DIY home decorators as well as children in need of a creative and educational toy. The kit relied on imagination, patience, and understanding of physics, and therefore it didn’t quite stand up against the more free form toys of the day. The project was abandoned, but it did help Rickey reach out to a younger audience, bolster his image as an educator, and form a bridge to art-making workshops and museums. Not long after, Rickey moved further into the concept of “kinetic” sculpture beyond mobiles. “I had to wonder whether Calder had said it all; when I found he had not, I had to choose among the many doors I then found open.” –George Rickey, 1979