Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles (Part 2)

As a professional mobile sculptor, I continuously study other artists’ work who have also explored the art form of mobiles. On this page I’m summarizing some of the research I have done for myself. Also, this is a continuation to my previous post Mobiles before Calder – A History of Mobiles (Part 1), in which I wrote about mobiles (or mobile-like sculptures) throughout history up until the early 1930s, when Alexander Calder started to make them. This second part focuses on sculptors who have expanded the art form of mobiles from the 1930s on to present day.

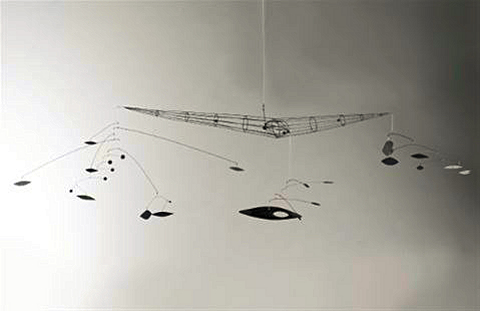

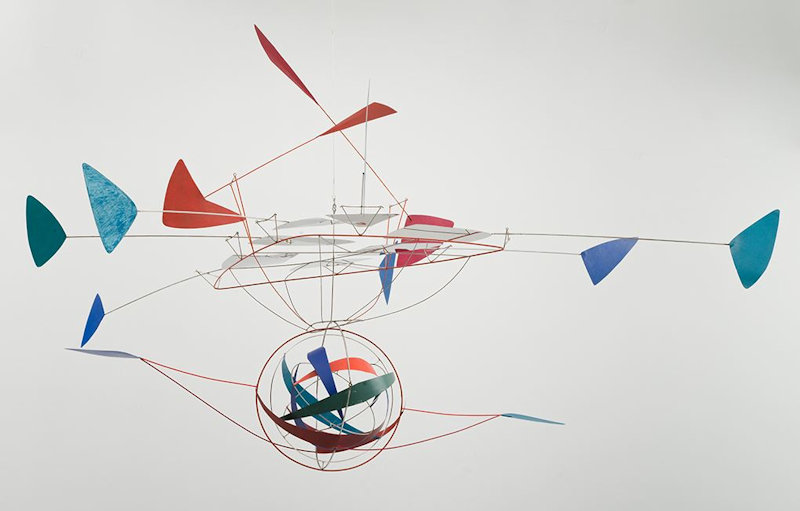

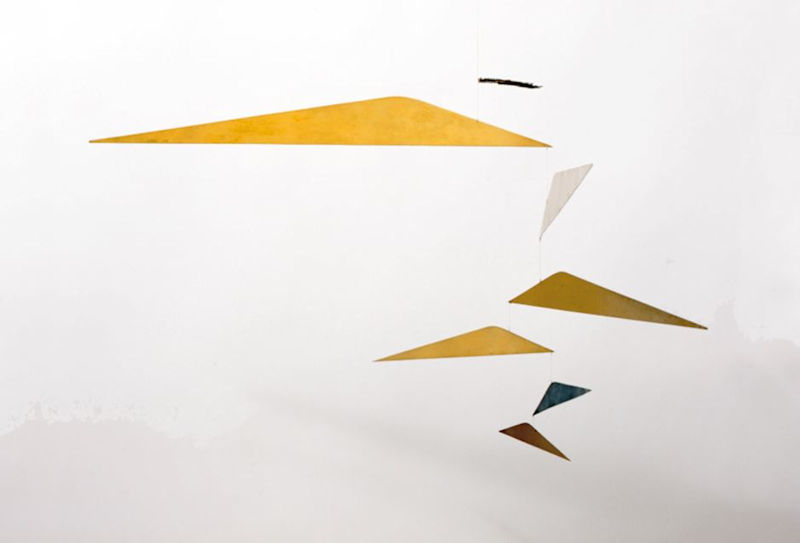

Probably anyone who is familiar with mobiles as an art form knows of Calder’s work. After all, he is widely regarded as the originator of the genre, which he continues to dominate even to present-day. “Calder is a school of one”, the Daily News announced in 1972. Art critic and Los Angeles Times contributor David Pagel referred to mobiles in a Los Angeles Times article in 2012 as “a genre of sculpture [Calder] may not have invented but owns so completely that it’s almost impossible for another artist to make a mobile and not be compared, unfavorably, to Calder.” As someone who makes mobiles professionally, I believe that there are vast uncharted territories in the art form of mobiles. The balance structure of a mobile (the whippletree mechanism) is like a few simple chords on an instrument: simple, but the possibilities of what can be done with it are infinite.

Not many sculptors have applied themselves yet to the relatively new art form of mobiles over the past 100 years. However, some mobile sculpture artists (besides Calder) have created new creative approaches and expanded the art form of mobiles since the early 1930s:

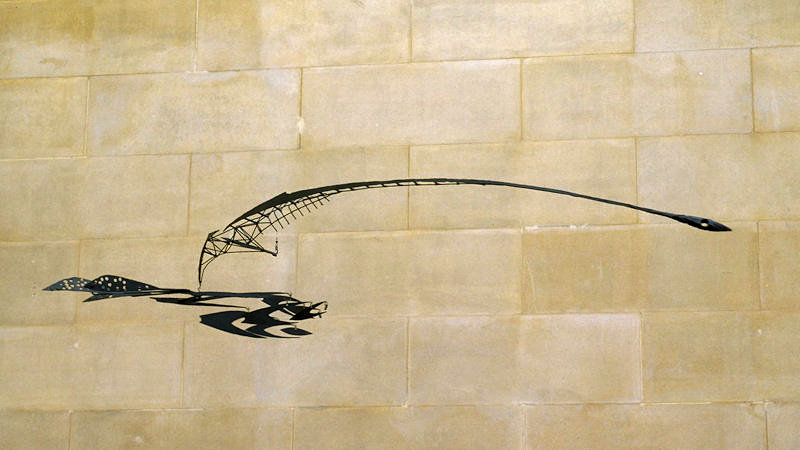

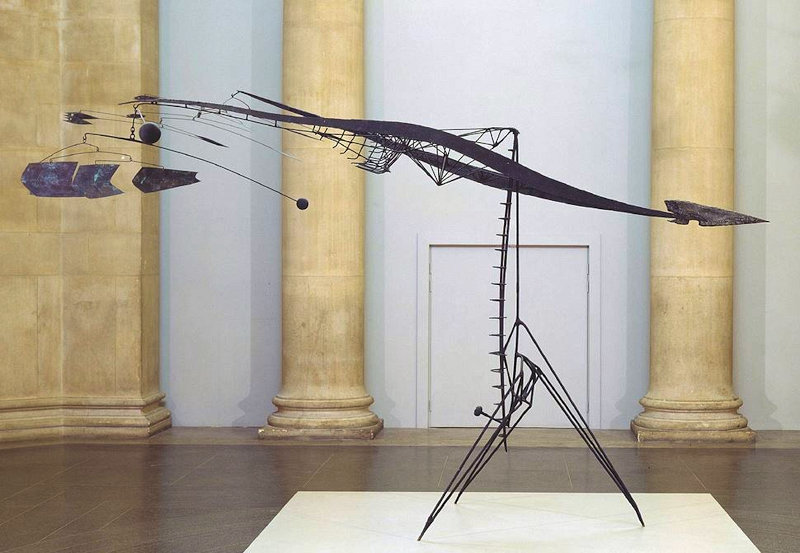

Lynn Chadwick (1914-2003)

Lynn Chadwick was an English sculptor and artist. A self-trained yet extremely skilled craftsmen in metal, he is regarded as one of the major figures in the arts of the second half of the 20th century. While working with architect Rodney Thomas, he made at least sixty mobiles between 1947 and 1952, of which some were suspended and others freestanding. While Calder usually hand-cut rounded and oval painted shapes, and spaced them out in evocative patterns on simple wire frameworks, Chadwick’s geometric, interlocking shapes appeared to be cut from a single sheet and, in the 1951 mobiles, anchored by an elaborate, rigid, constructed framework made of wire, balsa wood, copper and brass. Very few of these mobiles survive. Interestingly, Chadwick always insisted that he had no knowledge of the mobiles that Calder made for 20 years previous to his, but that his mobiles had evolved in his own style from his work on exhibition stands:

Later in his career, Chadwick would commented: “So I did this suspension idea, and it took a long long time till I realized that I was doing exactly the same thing as Calder, but this was just about the time when I gave it up, because I realized that Calder was, really, better at doing what he was doing, than I was at what I was doing.”

His son Daniel Chadwick makes mobiles as well.

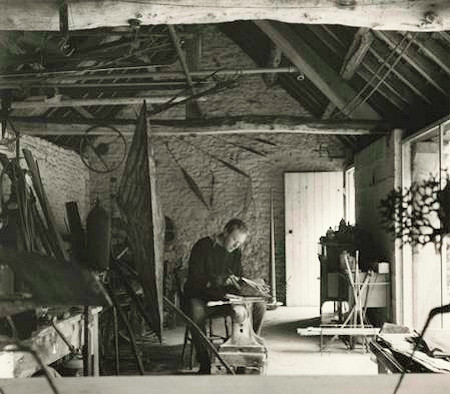

A mobile appears to be hanging on the wall in the back in Lynn Chadwick’s studio:

George Rickey (1907-2002)

George Rickey was an American kinetic sculptor. Originally inspired by Calder’s mobiles and having served as an engineer in the Army Air Corps in World War II, he is well known for his innovative standing kinetic sculptures that respond to the slightest air currents, and whose simplicity and scale made him an important figure in contemporary art. Around 1954, he began to wonder whether Calder, brilliant and varied as his mobiles were, had said it all. “When I found he had not, I had to choose among the many doors I then found open.” Whereas in Calder’s mobiles the motion of one part is almost invariably dependent on the motion of another (usually neighboring) element, the elements in Rickey’s work are no longer hierarchical but of equal status and able to move independently and randomly in relation to each other. In George Rickey’s obituary in 2002, Ken Johnson wrote in The New York Times: “Mr. Rickey was one of two major 20th-century artists to make movement a central interest in sculpture. Alexander Calder, whose mobiles Mr. Rickey encountered in the 1930’s, was the other.” He added: “It is a curious fact of contemporary art history that Mr. Rickey left no significant artistic heirs … no sculptor has adopted his innovations with comparably persuasive ambition or elegance.” I would think Tim Prentice (see below) would strongly qualify as a significant artistic heir, as well as perhaps Susumu Shingu, and more recently Phil Price, Pedro S. de Movellán and Michael Christoph Ernst. As to Rickey and mobiles, he made them as a child already and kept returning to the art form (although after around 1950, he often opted for standing kinetic sculptures instead of suspended ones):

A standing mobile:

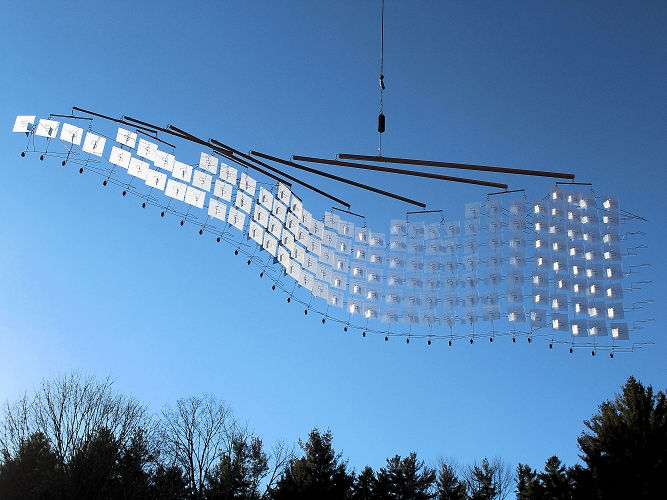

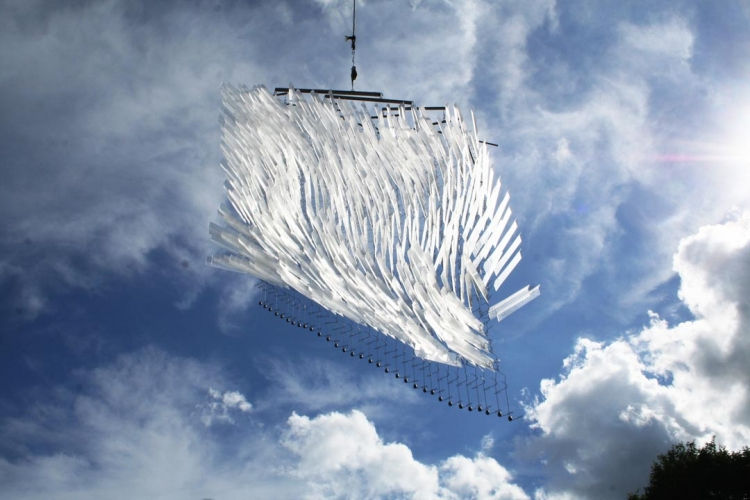

Tim Prentice (b. 1930)

Tim Prentice is an American architect and kinetic sculptor. Beginning in the 1970s, his work grows out of the tradition of Alexander Calder and George Rickey, both of whom he met, but it became something very original and fascinating of its own, or as he recently put it “I claimed some new territory because there was more turf to be explored”:

See a short film At Work with Tim Prentice- A studio visit with kinetic sculptor Tim Prentice.

Bruno Munari (1907-1998)

Bruno Munari was an Italian artist, designer, inventor, and author. He was interested in creating pieces of art that could interact with their environment, and made what he called “Useless Machines” (macchine inutili) of which many were essentially mobiles. Very similar to Calder’s thought process when he started to make mobiles, Munari thought that instead of painting geometric forms, why not free them from their static state and suspend them in the air:

The following suspended sculpture by Munari seems related to Ruth Asawa’s looped wire sculptures that she made only a short number of years later:

Jerome Kirk (1923-2019)

Jerome Kirk was an American sculptor. After earning a degree in mechanical engineering from MIT, he has made sculptures that measure over 45 feet in height and weigh over 6 tons, exploring a wide variety of kinetic sculptures including mobiles, both suspended and standing:

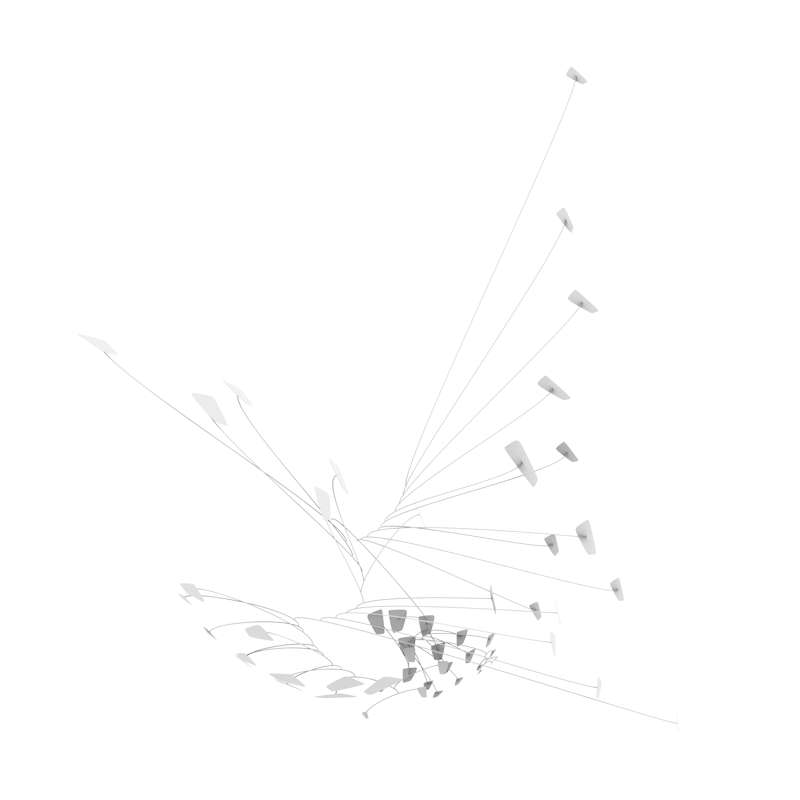

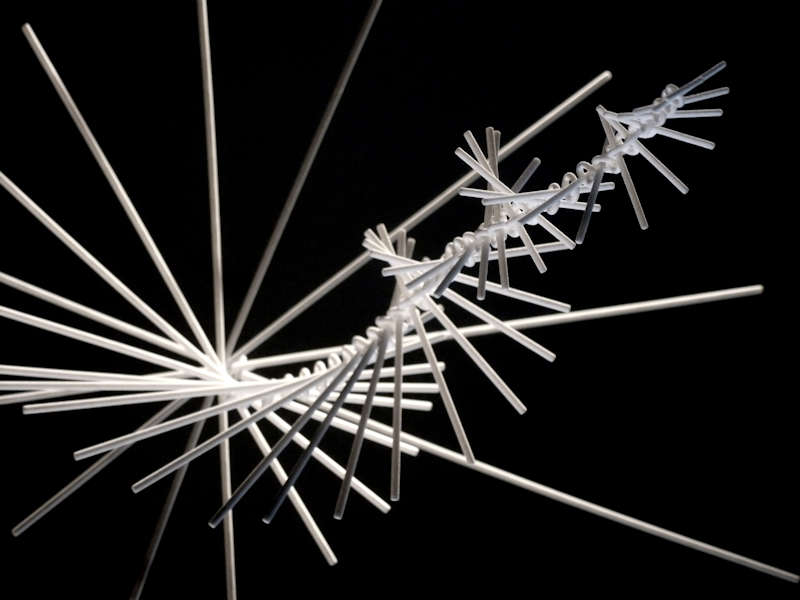

Marco Mahler (me)

I would certainly not be so arrogant to see my work as comparable to the artistic accomplishments of the other sculptors listed here, however, as opposed to just create mobiles “in the style of Calder”, expanding the art form of mobiles with new creative approaches and techniques has been the underlying motivation and passion for me in my work. I’d like to think that I’m in the process of succeeding with this, from my fully three-dimensionally designed mobiles that I’m currently working on, to the deconstructivist (?) contemporary mobiles, to the fully 3d-printed mobiles that I created in a collaboration with Henry Segerman, all of which are ideas in progress that I’m working on expanding:

Philippe Hiquily (1925-2013)

Philippe Hiquily was a French sculptor and designer. After attending Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, including workshops by sculptor Jean Tinguely, he went on to make a wide variety of sculptures and furniture, including mobiles:

Additional mobile sculpture artists (besides Calder) to be added to this list who have created new creative approaches and expanded the art form of mobiles since the early 1930s would be: Laurent Martin “Lo”, Philippe Jestin, Derick Pobell, Yuko Nishikawa, Steve Haas (who combines multiple levers within one object), Jade Oakley, Brad Howe and Dylan Davis and Jean Lee.

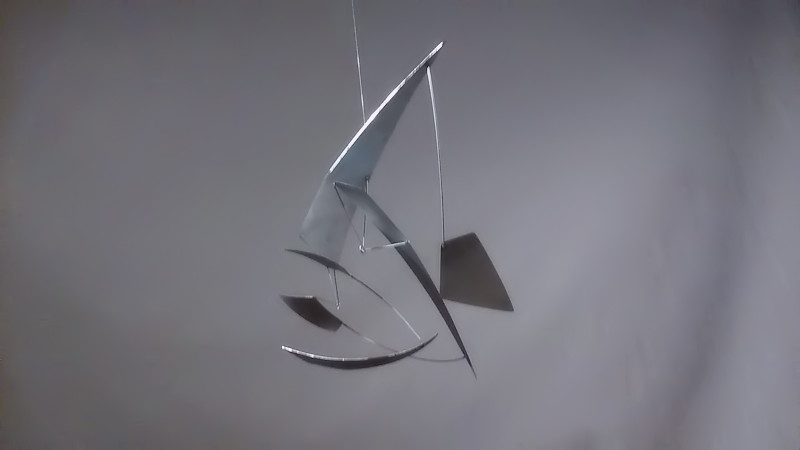

The following suspended sculptures don’t qualify as mobiles in a strict sense, because they don’t utilize the interconnected balance structure (a whippletree mechanism as in a Calder mobile) that distinguishes a mobile from simply a suspended kinetic sculpture. However, I think the sculptures by these artists are closely related to mobiles and would be important to add to this list:

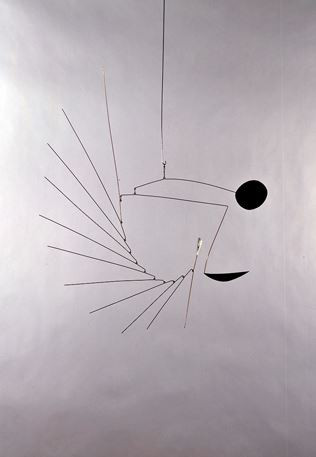

Kenneth Martin (1905-1984)

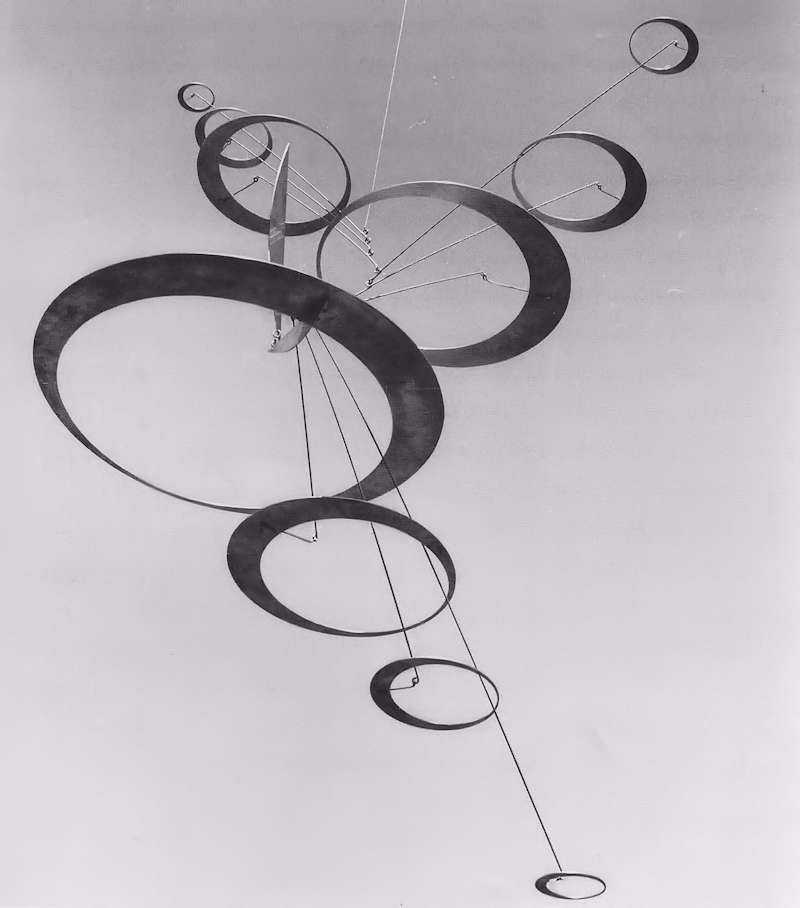

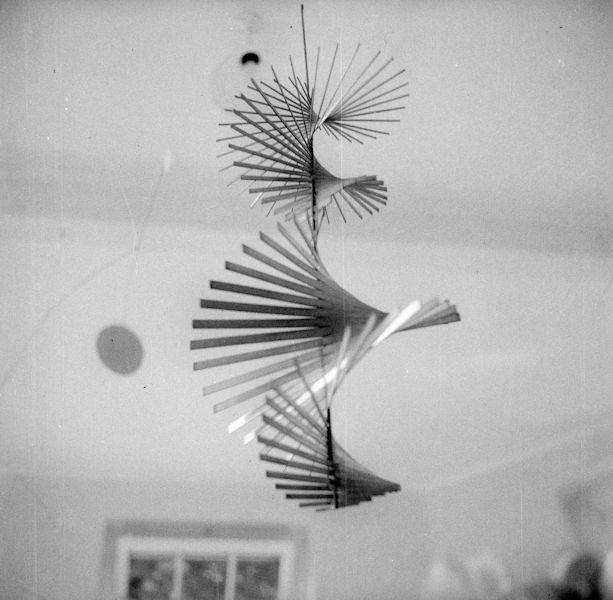

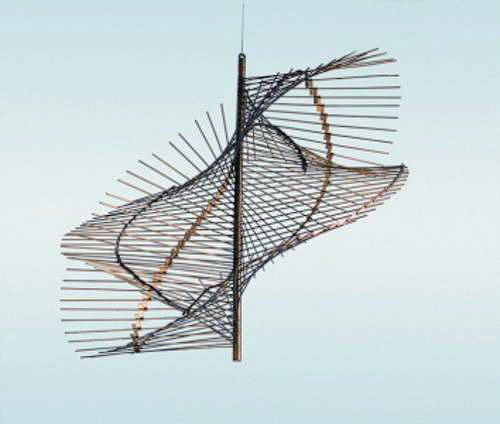

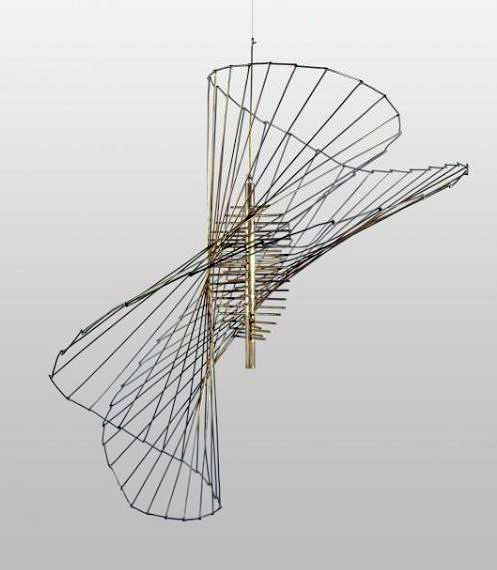

Kenneth Martin was an English painter and sculptor who (with his wife Mary Martin and Victor Pasmore) was a leading figure in the revival of Constructivism. After focusing on portraits and landscapes, his interest turned to Kasimir Malevich‘s art and geometric abstraction, which he also applied to mobiles and kinetic sculptures beginning in the early 1950s:

Among contemporary mobile artists, Miranda Watkins’ mobiles appear to be taking a similar approach as the above mobile, as well as some of the 3d printed mobiles I created in a collaboration with mathematician Henry Segerman.

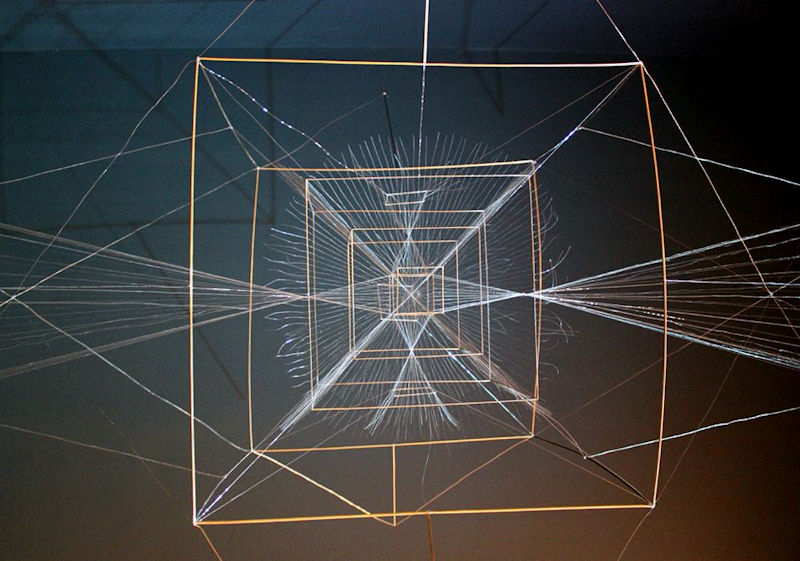

Richard Lippold (1915-2002)

Richard Lippold was an American sculptor known for his geometric constructions, often relating to Cubism and Constructivism. His suspended sculptures may not qualify as mobiles, but I like them too much to not include them in this list. He spent decades stringing wires across rooms, working with architects like Walter Gropius, creating hanging sculptures that measured over 100 feet and consisted of miles of wire. The below pictured “Orpheus and Apollo”, which used to be installed at Lincoln Center, was possibly one of the largest works of public art in New York City.

In 2014, it is was dismantled for maintenance and conservation, and it will not be reinstalled at its original location. Instead, the sculpture will be suspended as the centerpiece of La Guardia Airport’s Central Hall, which is set to open in 2022.

Update – October 2023: The five-ton sculpture has been reinstalled from the ceiling of the new glass-enclosed Atrium Business and Conference Center at La Guardia (connected to Terminal B’s arrivals and departures hall) that opens next week to the public.

If you like Richard Lippold’s work, take a look at Pae White‘s work.

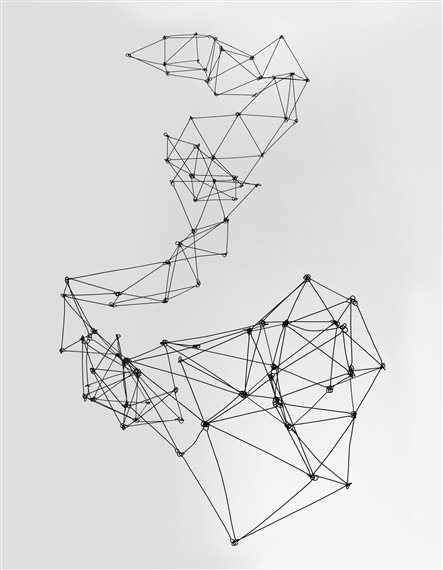

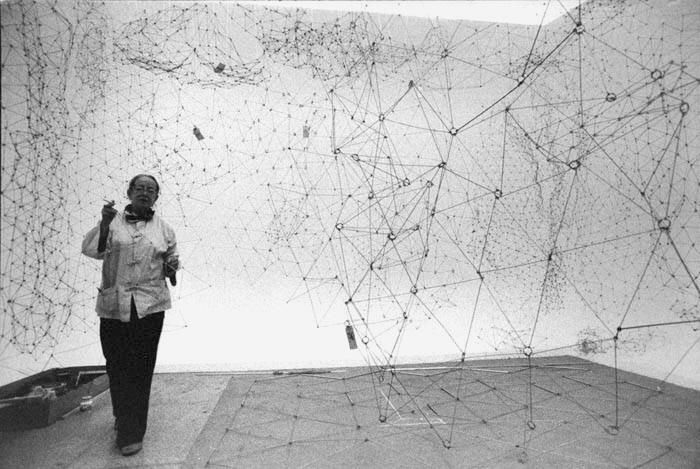

Gertrud Louise Goldschmidt (1912–1994), more commonly known as Gego

Gego was a modern Venezuelan artist and sculptor. I wouldn’t consider her suspended kinetic sculptures necessarily to be mobiles, at least not the ones that I’m familiar with. Yet I think the breakthroughs she contributed are, and will be, very significant to the art form:

Be sure to also take a look at the amazing work by Elias Crespin (her grandson).

Additional sculptors whose work is related to mobiles (even though their work doesn’t qualify as mobiles in a strict sense because they don’t utilize the interconnected balance structure based on the whippletree mechanism) would be: Tomás Saraceno, Elias Crespin, Reuben Heyday Margolin, Julio Le Parc, Pae White, Paul Vexler, Ralph Helmick, Hitoshi Kuriyama, Leon Jakimič (founder and owner of Lasvit), Fausto Melotti, Neil Dawson, Jean Tinguely, Antony Gormley, Matt McConnell, Jonathan and Evelyn Clowes, Mel Ristau, Ralfonso “Ralf” Gschwend, François Morellet, Jesús Rafael Soto, Ruth Asawa, Hirotoshi and Nami Sawadaand, Sarah Sze and Kendall Buster (my work space neighbor a few doors down).

Calder’s work, along with mobiles in general, has recently received renewed attention and interest, partly due to the Calder Foundation‘s excellent management of Calder’s body of work and arrangements of brilliant shows worldwide. His mobiles keep setting new records at auctions, selling in the tens of millions of dollars. In 2014, the Art Newspaper wrote about that year’s world-renowned art fair Art Basel in Miami Beach: “The number of mobiles by Calder and other artists on galleries’ stands is striking. Among the works by the hundreds of artists brought by 267 galleries from 31 countries, mobiles definitely constitute a trend.”

Aside from the art form of mobiles, Calder was also a pioneer in making wire sculptures starting in the 1920s, making portraits out of wire of public figures, entertainers, close friends and himself. He also made wire sculptures for his Cirque Calder and of animals, often sprinkled with a bit of humor. One story has it that Calder presented himself at an exhibition venue at Harvard with no work. According to Calder, the gallery director “protested that I arrived with nothing but a roll of wire on my shoulders and pliers in my pockets”. By the time the show opened a few days later, Calder had created all the works for the show on the spot, while interacting with gallery personnel, patrons, and friends. Artists such as Ruth Asawa, Kendra Haste, Sophie Ryder, Edoardo Tresoldi, Kue King and Tomohiro Inaba have expanded the art form of wire sculptures since.

I’ll be adding to this list from time to time. As a continuation, please see my page Contemporary Mobile Sculptures – Expanding Calder’s Art Form.

This article was originally published on my blog here on this website in 2017. As with anything on my website, if you have any suggestions, anything that should be added, corrected, or have any questions or comments, please let me know.

Related:

Artsy article: 7 Artists Who Created Innovative Mobiles—beyond Alexander Calder

New York Times article by Nancy Hass: How Artists Are Challenging Alexander Calder’s Mobiles