Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles (Part 1)

As someone who makes mobiles professionally and has spent quite a lot of time studying mobiles, I get asked once in while, where did mobiles originate from? Who made the first mobile? Or, who invented mobiles? The short answer is that Alexander Calder is the originator of mobiles, which is mostly correct, but Calder wasn’t the first one nor the only one to experiment with the art form. The problem with providing a definite answer to the question of who made the first mobile starts with the definition of what a mobile is, and what is simply just a hanging kinetic sculpture made of individually suspended objects rather than being constructed with an interconnected balance structure that defines a conventional mobile. You can read my definition of what a mobile is on my main page, but there isn’t really a set of rules that one can apply to clearly tell one from the other. The first person, that I’m aware of, to clearly utilize the interconnected balance structure in a suspended sculpture wasn’t Calder. It was Man Ray with his piece titled Obstruction made of coat hangers in 1920, 10 years before Calder started to make mobiles. Man Ray also met Calder in Paris in the late 1920s, attended a performance of Cirque Calder in June 1929, shortly before Calder started to make mobiles, and made portrait photos of Calder around the same time . And there a examples of suspended sculptures before Man Ray’s piece that began to explore the idea of an interconnected balance structure. Following are the hanging kinetic sculptures that I’m aware of that were made before Calder started to make mobiles. Some of them clearly qualify as mobiles in my opinion, others are up for debate.

In chronological order:

I’ve heard of a Greek architect who built a floating statue in the 2nd century B.C. for the wife of Egyptian King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (B.C.284-246). The suspended sculpture was dependent on the overall setting of magnetic forces on the roof and the walls. I’ve been trying to find out more about this but without success.

Wind chimes have probably been around since prehistoric times. The first evidence of them, found at archeological sites in South East Asia, dates them to about 3000 B.C.. The oldest one I have been able to find an image of is from ancient Rome where people made them out of bronze. They called them Tintinnabulum and hung them outdoors so the wind would make the bells ring. They were also believed to ward off evil spirits.

Himmelis are traditional sculptures that originated in Finland, although the root of the name is Germanic. They are a decorative objects, usually made of straw, that hang from the ceiling. A Himmeli (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) is usually symmetrical and pyramid-shaped and rotates slightly with the air flow. Traditionally, they were made in the fall and were placed above the dining table until summer to ensure a good crop for the coming year. I haven’t been able to find out how far back in history the tradition goes, but they have definitely been around long before 1930 when Calder started to make mobiles.

If you’d like to make a Himmeli yourself, the Guardian has a How To Make A Himmeli Sculpture.

The Museum Van Het Nederlandse Uurwerk in Zaandam, Netherlands has a mobile dated to 1751 made of four small whale hunter boats circling a whale:

Calder was also interested in 18th century toys that demonstrate the planetary system.

From 1918 through 1921, Russian artist Aleksandr Rodchenko made some of the first suspended kinetic sculptures of the 20th-century with three series of spatial constructions, each comprised of six works. Regrettably, most of them have long been known only through photographs made at the time and through Rodchenko’s own sketches on a page of his notebook. Here is his Oval Hanging Construction No.12:

He considered them “lab work” rather than art objects and were made to demonstrate theoretical concepts.

Rodchenko’s suspended sculptures at the Second Spring Exhibition of the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) in Moscow in 1921:

The Russian sculptor Naum Gabo began to experiment with kinetic sculptures in 1917, which makes him a pioneer in the art form. He was interested in making sculptures that continually change their appearance, but are constant in what they represent (much like mobiles). The majority of his work was lost or destroyed, but here is a 1918 drawing that he titled Sketch for a Mobile Construction:

In 1915, Russian painter and architect Vladimir Tatlin made a suspended sculpture called Contre-Reliefs Liberes Dans L’espace. Constructed of mathematically interlocking planes, it apparently looked like a mobile. The details surrounding Tatlin’s life and work are relatively obscure. Here is his Letatlin (1930):

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Naum Gabo and Vladimir Tatlin (who all knew each other) were pioneers of the art movement known as Constructivism, a term that first appeared in Gabo’s Realistic Manifesto of 1920. The movement had a great effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. On the topic of Calder and Constructivism, Jed Perl notes in his biography of Calder: “Commentators who knew Calder in the 1930s, most significantly James Johnson Sweeney and Alfred Barr, argued that he owed a significant debt to the work done by the Russian avant-garde in the years before and after World War I, work often characterized by the artists and their supporters as Constructivist. Rodchenko’s hanging sculptures, Tatlin’s Monument on the Third International, and works by Gabo were mentioned. Even earlier, the German critic Adolf Behne, writing about the Neumann-Nierendorf show in 1929, had related Calder’s work to the experiment of the Russian Constructivists. But there is a problem with the genealogy of Calder’s first abstract works as it was articulated by Barr and Sweeney. As early as 1934, in a letter to the collector Albert Gallatin, Calder asserted that he had known nothing about any of these works or for that matter about Constructivism in general until Hélion told him about all of it in 1933. Surely Calder’s own testimony that pushed his friend Sweeney, in 1938, to observe that although Calder’s work was “built on a Constructivist foundation,” the artist “nevertheless had no connection with Russian Constructivism except in the fundamentals of its structure” – a statement that, to say the very least, is hard to parse. To the end of this life, Calder insisted that he had known nothing about the Constructivists in 1931. Sometime in the 1960s or 1970s, in a letter to a young art historian, Nanette Sexton (who also happened to be his grand-niece), Calder observed that “crabby guys before this have said that I must have known about the Russian Constructivists – but it’s quite untrue, i.e. I knew nothing about them till after having made some of my first mobiles.”

Now this next one is very important for the history of mobiles. It’s Man Ray‘s Obstruction that he made in 1920. It employs the whippletree mechanism as a balance structure in the same way that Calder started to use it in some of his mobiles a decade later. The whippletree mechanism probably dates back to between 190 to 209 AD, and has been used to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon:

Man Ray’s Obstruction is the first of this type of hanging kinetic sculpture that I’m aware of that makes use of this mechanism. Even with it’s rudimentary coat hanger design, it can definitely be classified as a mobile:

And just because it’s so important to the evolution of mobiles, here’s another photo of it (63 wooden hangers, recreated in 1961):

As mentioned above, Man Ray met Calder in Paris in the late 1920s, attended a performance of Cirque Calder in June 1929, shortly before Calder started to make mobiles, and took portrait photos of Calder around the same time. Here are Man Ray’s instructions on how to assemble his mobile:

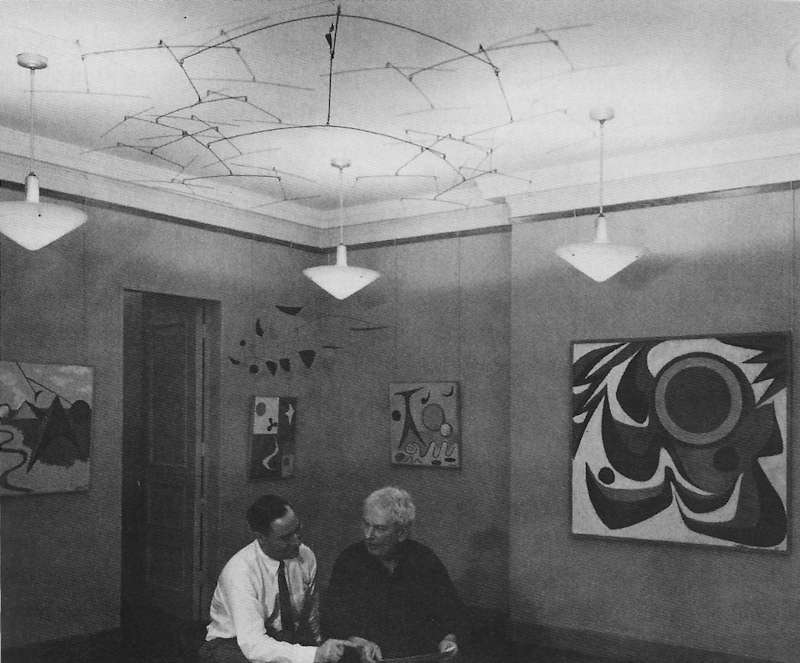

Here’s Calder (with Klaus Perls) at Calder’s 1956 exhibit at Perls Galleries with his mobile Untitled (Mobile with N Degrees of Freedom) that he made in 1946 suspended from the ceiling, which is essentially the same sculpture as Man Ray’s Obstruction (1920), just made with wire instead of coat hangers:

Many years later in 1974, Calder also created a tribute to Man Ray for a suite of prints, Hommage à Man Ray. As noted by the National Portrait Gallery: “With its odd assortment of images, this tribute to the eighty-four-year-old Man Ray reads like a private joke between two friends. Calder fondly recalled his early days in Paris when he hung out with “quite a gang,” which included Man Ray and Kiki, the “Queen of Montparnasse.”

Man Ray also experimented with hanging abstract pieces of sheet metal, here with his Lampshade in 1920:

Bruno Munari, one of the first kinetic sculptors, started to follow the Futurist movement in 1927. He made what he called “Useless Machines” (macchine inutili) and was interested in creating pieces of art that could interact with their environment (much like mobiles).

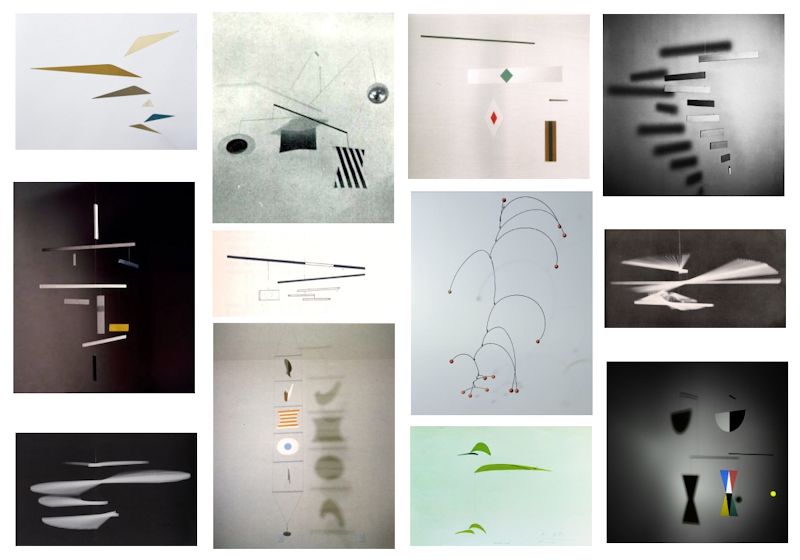

Bruno Munari’s Macchina Aer0ea (aerial machine), 1930:

Bruno Munari continued to make very beautiful and original mobiles throughout the 1930s and 1940s (same time frame as Calder was exploring the art form):

Bruno Munari once said (from the book Bruno Munari: Air Made Visible): “What difference was there between my useless machines and Calder’s mobiles? I think I should clear up this matter: apart from the fact that the material construction was different, the means of constructing the objects was also different. The only thing they have in common is that they are suspended objects that move. But there are many suspended objects and there always have been, apart from the fact that even my friend Calder had a precursor in Man Ray, who in 1920 constructed an object on the same principle.”

See more of Bruno Munari’s work if you’re interested, it’s quite amazing.

Paul Klee was reported by Lyonel Feininger to have had little mobiles in his Bauhaus (1919 to 1933) studio in Dessau, however, I’m unable to find any additional information nor images of them.

According to the Museum of Modern Art, one of Alberto Giacometti‘s achievements was to enlarge the mobile concept decisively, so that formal innovation could be reconciled with the Surrealist interest in subconscious associations. Here is his kinetic sculpture, Suspended Ball, 1930:

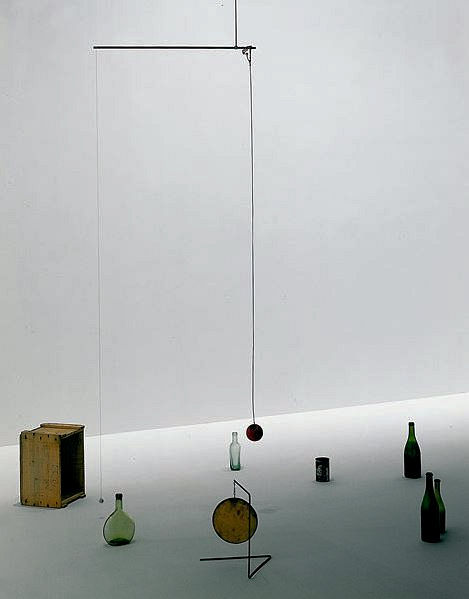

And now here comes Alexander Calder in 1931 experimenting with abstract motorized constructions like Mobile (Motorized Mobile):

Calder visited the painter Piet Mondrian in October 1930 and later said: “When I looked at his paintings, I felt the urge to make living paintings, shapes in motion.” Influenced by the abstract work of Mondrian, Joan Miró and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, he’s approaching the idea of kinetic sculptures like an alchemist with pieces like Object with Red Discs (also known as Calderberry Bush even though Calder claimed he never assigned that title to it), made in 1932 and regarded as his first standing mobile:

And considered by some to be his first hanging mobile (and also one of his rarer sound / “noise” mobiles), Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/33):

And in 1933, Cône d’ébène, one of his first hanging mobiles where all the elements are suspended:

Calder made a simple yet very important advance in how the balance structure is applied to a hanging kinetic sculpture. He went from the straightforward whippletree structure, like the one in Man Ray’s Obstruction mobile that we looked at above, to this (Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1932):

Instead of attaching lower elements to both ends of the wires, he replaces one on each arm with an abstract shape. It’s a new way to apply the whippletree structure to a hanging kinetic sculpture, which allowed him to turn the whole idea into a new art form, a complete new magical universe with mobiles like Vertical Foliage (1941):

The term “mobile”, a French pun meaning both “mobile” and “motive”, was coined by the master inventor of Dada, Marcel Duchamp, while visiting Calder’s studio in 1931, although he apparently already used the term in 1913 for his readymade Bicycle Wheel, which some consider to be the first kinetic sculpture.

On the topic of art theory, Calder said, “My whole theory about art is the disparity that exists between form, masses and movement”, and that “there is no idea I want to express – no meaning. What I have tried to do is just create something interesting to look at”. He avoided overly analyzing his work, believing that “theories may be all very well for the artist himself, but they shouldn’t be broadcast to other people.”

George Rickey wrote in his review of Calder’s retrospective at London’s Tate Gallery titled Calder in London in 1962: “Calder’s fame and place in history have been secure for a long time. Outside his country, he is the most famous American artist … In Holland any moving sculpture is called “a Calder.” … Though he did not invent moving sculpture, he demonstrated to critics, historians, collectors, the man in the street, and to other artists, that it was inevitable. One need not dwell on the endless imitations and perversions of his inventions and of his style. He has delighted the world. But with what? What is he? Is he good? Is he, though a success as a popular entertainer, a superficial artist? Is he the lucky (or unlucky) stumbler on the right thing (getting sculpture into the air) at the right time, who has been trapped by his luck, or is he one of the great innovators of the epoch? Is he possibly a frustrated painter, able, through a mechanical device, to make a reasonable facsimile of sculpture? Why does a lot of Calder seem less impressive than a single piece? Is there a Calder myth?”

If you know about any other early mobiles, standing or hanging, or suspended kinetic sculptures that were made before the early 1930s, please let me know, I’d love to hear from you.

This article was originally published on my blog here on this website in 2014. Modified versions of this article also appear on Houzz, Saatchi Art (via Artsy on FB and Twitter and via Saatchi Art on FB and Twitter), Widewalls and WIRED.

Forbes article linking to this article: Seattle Art Museum Becomes the Alexander Calder Destination with Shirley Family Collection

Next: Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles (Part 2) – a list of sculptors and specifically mobile artists (besides Calder) who have made important contributions to the art form since the early 1930s.

Artsy article: 7 Artists Who Created Innovative Mobiles—beyond Alexander Calder

Related article on My Modern Met: Art History: The Evolution of Hypnotic Kinetic Sculptures

New York Times article by Nancy Hass: How Artists Are Challenging Alexander Calder’s Mobiles

– See some of my mobiles or read more of my blog about mobiles –